…why future-fit businesses are ditching disposability and designing for durability instead.

The research is clear: people want good quality, affordable things that make their lives better. Customers are NOT demanding lower quality, lack of repair options and gradual reductions of product lifetimes. And yet, in a bid to increase revenues in a competitive market, companies keep pushing out ‘new and improved’ products. But designing for early obsolescence – whether physical, emotional or perceived – can backfire.

It’s time for a return to democratic, resource-intelligent designs, that help us do better, with less.

9 minute read

Good quality things that make life better

Over half the global population is now experiencing global heating first-hand, with 42% saying they were now greatly affected by extreme weather. Sustainability is more important to 70% of people than it was just two years ago, driven by increasing awareness of the effects on health, safety and future generations, combined with cost of living pressures. That awareness is fuelling action: a major survey across 17 countries found that 85% had shifted towards being more sustainable in the five years leading up to 2021.

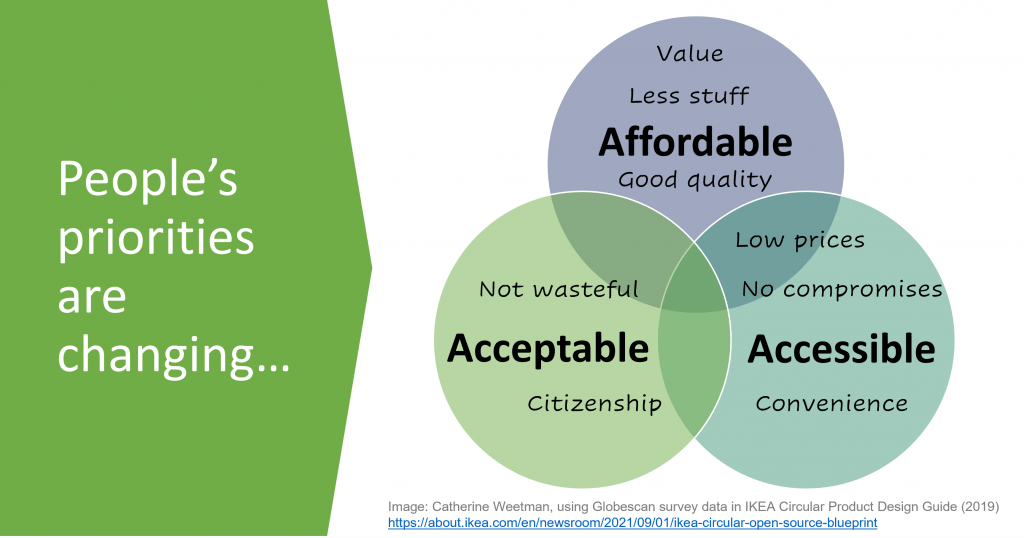

People’s priorities and worldviews are evolving, affecting lifestyles and the nature of relationships with things. Research by IKEA and GlobeScan finds that having more, having the latest, is less important, and 84% of people feel bad about throwing things away. IKEA highlights five main considerations for customers:

- Value plays a big role: people want less stuff and want the things they choose to be as good as possible.

- Affordability means low prices without sacrificing function, quality, design or sustainability.

- Convenience is important, but can be a barrier to caring for, and circulating our stuff.

- There is a growing awareness about consumption and sustainability, and people don’t want to be wasteful.

- People want to be good citizens, contributing to a better society and planet.

Affordable, accessible and acceptable

We could sum this up with three watchwords: things should be affordable – providing value and quality; accessible and convenient, making it easy for everyone to have a good life; and acceptable – good for them personally, good for wider society and the environment.

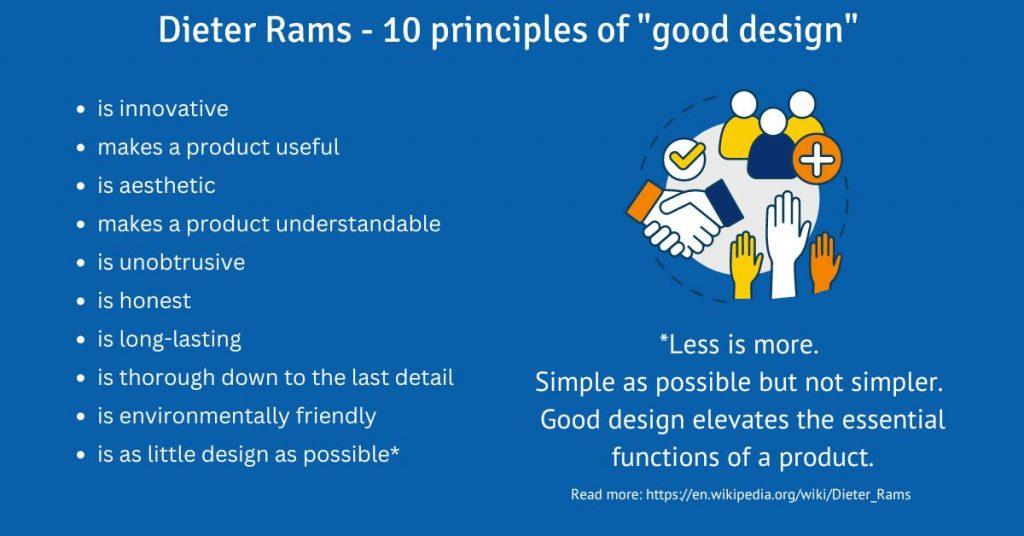

Back in the 1950s, good design was seen as democratic, enabling mass-production of useful products at reasonable prices, perhaps best portrayed by the celebrated German industrial designer Dieter Rams’ and his mantra, ‘Weniger, aber besser’ which translates as ‘Less, but better’.

But since that heyday of democratic design, ‘better’ has become synonymous with ‘cheaper’, driven by a belief that business success means getting bigger: trying to grow revenues by selling more stuff, to more people, year after year. Cat Drew of the Design Council sums it up: “mass consumerism created a tonne of stuff that failed to recognise the need for longevity of things.” Andrew Johnson, a product design specialist at Loughborough University agrees, noting that “we now have too much stuff that can be manufactured without much skill.”

However, the danger of designing things for the lowest cost means it’s easy for your competitors to copy, and it’s more difficult to differentiate and to make your product resonate with your customer. We’ve already noted that people want low prices without sacrificing function, quality, design or sustainability, they don’t want to be wasteful, and want to be good citizens, contributing to a better society and planet.

Less, but better feels like it should be a ‘design for life’, but it seems that most companies aren’t designing what their customers want.

Ever-shorter lifetimes and ever-growing footprints

In its research to understand how people engage in the circular economy, the European Parliament highlighted recent studies showing that ‘products nowadays have an ever-shorter lifespan, break down faster and are increasingly difficult to repair. A 2016 study by the German Environment Agency found evidence of shorter lifetimes for large household appliances: those replaced within the first five years of their service due to a defect increased from 3.5 % in 2004 to 8.3 % in 2013. Put simply, the level of early failures more than doubled, in less than a decade.

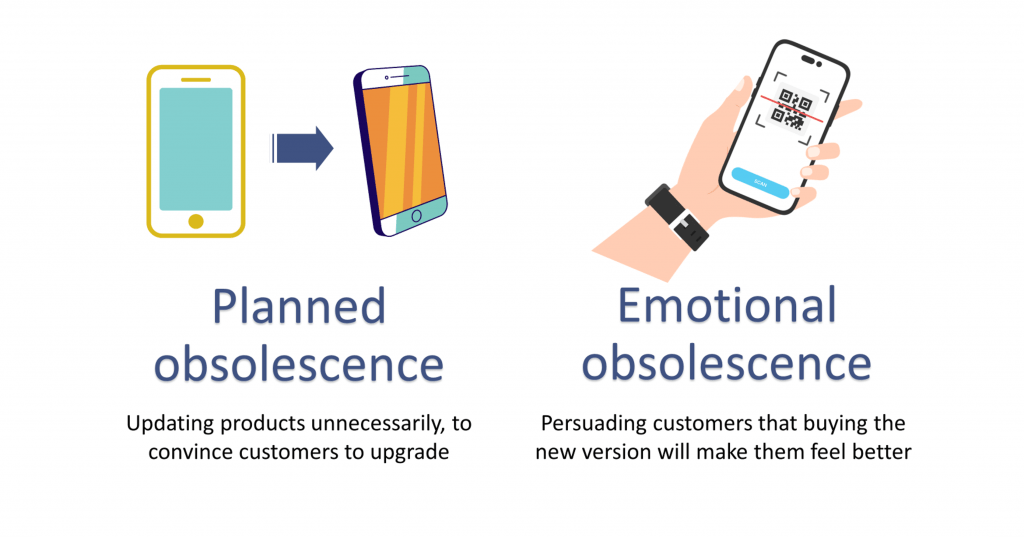

Whilst product failures and lack of repairability are a big part of the problem, intentional obsolescence is a major factor in the shortening of product lifetimes. The European Parliament lists five different causes:

- planned or built-in – products are designed to deliberately fail after a certain time or a number of uses;

- premature – products last less than their normal lifespan compared to consumer expectations;

- indirect – components required for repair are unobtainable, or it is not practical or cost-effective to repair the product;

- incompatibility – products no longer work properly once an operating system is updated;

- style obsolescence – leading consumers to believe that their products are out of date although they are still perfectly functional.

But these tactics can backfire. One study, looking at a range of consumer electronics, found that nearly 8% of people in five countries across central Europe said they didn’t attempt repairs as they had “lost faith in the brand”. Strategies based on shortening lifetimes risk eroding brand trust.

Live long and prosper!

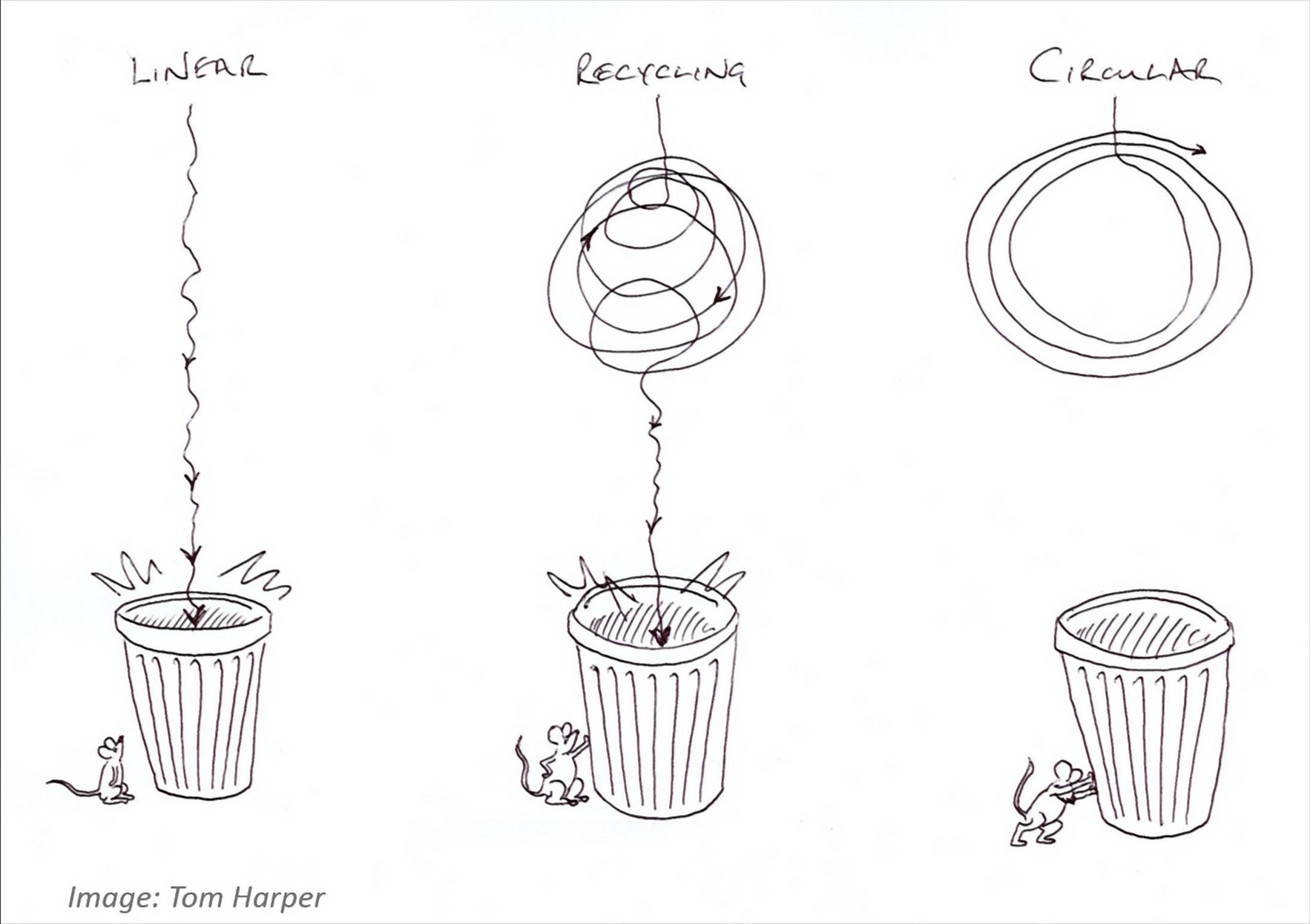

How can we rethink this, and help businesses do better, with less? If you’ve heard me talking about the 3 essential strategies for circular businesses, you’ll know that one of those 3 strategies is keeping things in use for longer. That means providing products that are durable, repairable and have resale value. It’s frustratingly difficult to find good examples of this, so I was happy to discover the Buy Me Once platform, which selects everyday products that are durable and repairable, and makes it easier for people to find and buy them.

Tara Button, Buy Me Once founder and CEO highlights the importance of designing for durability to meet the needs of a growing demographic who are pushing for longer-lasting, easily repairable products. Buy Me Once customers also encourage brands by giving feedback, to help raise the standards of what they offer.

Button’s early career in marketing and advertising unlocked valuable insights into the psychology of consumerism. She has built on in an engaging and insightful book on mindful consumption – A Life Less Throwaway. It includes some great tips to help people make more conscious choices, instead of getting sucked along by all-too persuasive marketing to ‘buy it now’.

Button’s book explains how product lives are shortened by ‘quality stripping’, with designers and procurement teams tasked to reduce the costs of making the product. This can include using lower quality materials, swapping to a cheaper component, using glues and bonding instead of removable fixings, and so on, all of which are likely to cause earlier failure or prevent cost-effective repairs.

Button’s business, Buy Me Once partners with hundreds of ethical brands to help consumers buy for the long term. It offers a wide range of products from kitchenware to bedlinen, home furnishings to electronics, and clothing. Products are sold in the UK and the United States, with some available for delivery in the European Union.

Designing products for life can be transformational. As management and quality theorist W. Edwards Deming pointed out, “profit in business comes from repeat customers, customers that boast about your project or service, and that bring friends with them.”

Designers want to be part of the solution (not the pollution!)

It must be demoralising to be asked, yet again, to find a way to reduce the cost of the product you designed. Instead, imagine how you’d feel about being challenged to make this more emotionally durable, easier to care for and repair, easy to upgrade, more multi-functional? Asking different questions of designers makes their job more meaningful and fulfilling.

Unsurprisingly, those studying design are pushing for change, too. Loughborough University’s Andrew Johnson has noticed changes since 2020, with sustainability now embedded in the mindsets of design school students: an essential part of being a responsible designer.

The influential industrial designer Dieter Rams, who worked with consumer products company Braun and the furniture company Vitsœ, set out ten principles for ‘good design’, including making a product useful, understandable, unobtrusive, honest, long-lasting and environmentally friendly. Rams introduced the idea of sustainable development, and of obsolescence being a crime in design, in the 1970s.

Emotional durability can be enhanced by encouraging people to be involved in assembling the product – the ‘IKEA effect’. Configuring the product yourself – even in a small way (such as clipping the back panel cover onto the Fairphone 2, or assembling a flat-pack furniture item), means you are much more likely to cherish it and care for it. Unsurprisingly, repairing or refurbishing has the same effect.

It seems obvious that good design should be affordable, accessible and acceptable. For the Design Council’s Cat Drew, ‘good design’ means material provenance, repairability, recyclability and fairness in supply chains, and can include favouring second-hand over new.

Less, but better

Some say that these surveys may reflect increased interest in sustainability, but most people will still want to buy the latest stuff. Yet times are changing. Inflation is front-of-mind for many, and the uncertainty of what’s around the corner is undermining people’s willingness to spend and borrow.

Mintel predicts that over the longer term, spending decisions are likely to be driven by key factors, including wellbeing, surroundings, technology, rights, identity, value and experience. A shift away from fast paced lifestyles and excessive consumption is showing up in slower, minimalist habits, with an emphasis on durability, protection and functionality. Plus, the rapid pace of urbanization and rising property costs mean space is at a premium: less space means buying less stuff.

Buy Me Once puts circular economy principles at the heart of product selection, selecting products and brands that meet high standards of durability and repairability, backed up by robust warranties. On top of their high-quality design and materials, these products often have great aesthetics and functionality, so we get a rewarding experience from using them. Looking for the weaknesses and failure points, from both the design and materials perspective, is a great way to get to the core of what customers will value.

Buy Me Once makes sure it lives up to its promise, too. If brands don’t continue to meet the standards and live up to their promises, they’ll be removed the platform.

Creating more value, with less

Button’s mission is for Buy Me Once to be a consumer champion, both to help people find the best stuff and to challenge manufacturers to do better. Buy Me Once aims to educate everyone about the importance of buying for the long term and keeping those products in use, including making it easier to fix things if they go wrong.

The Design Council still believes good design is central to economic success, and eco-principles can be compatible with mass production.

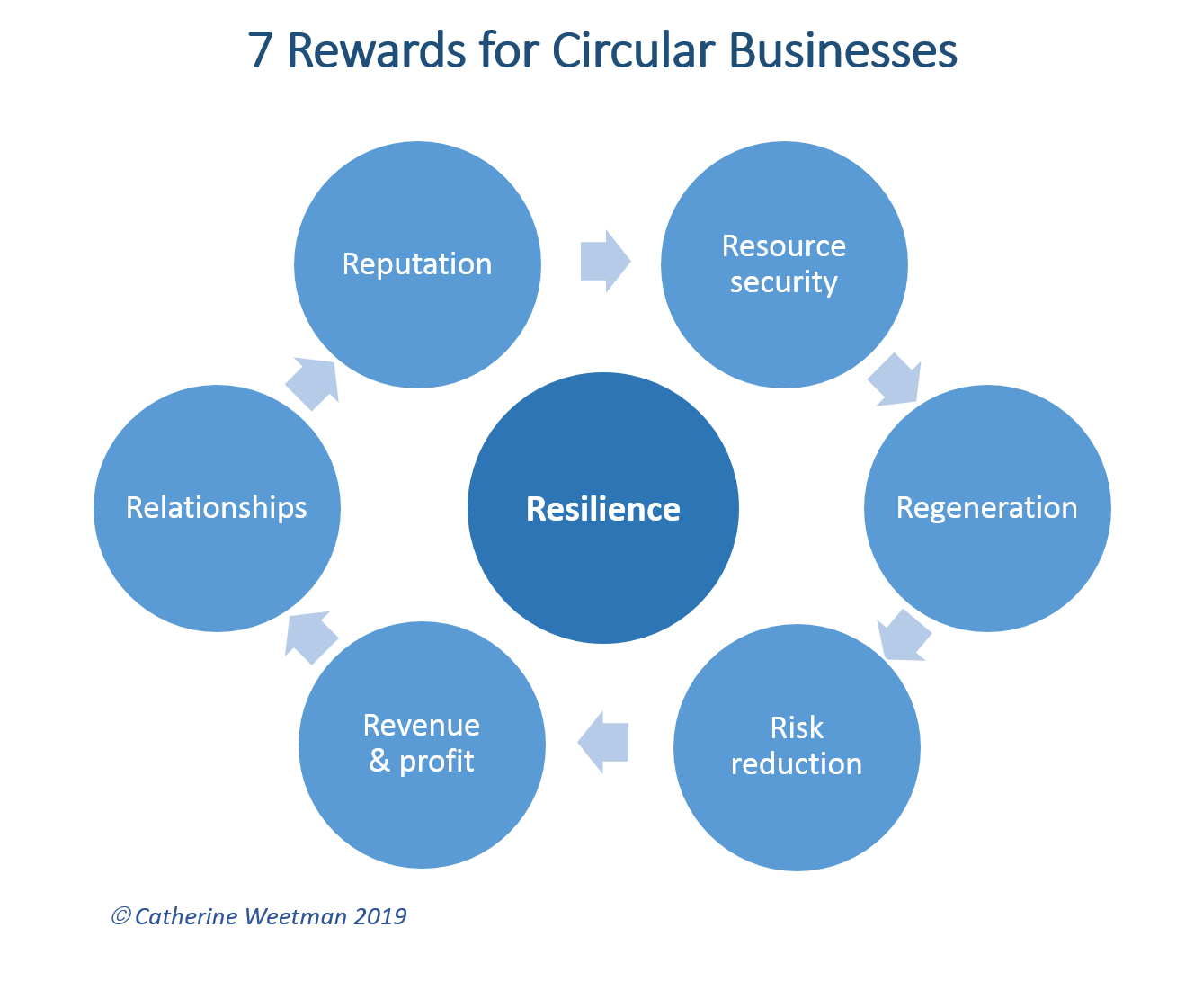

Designing for durability and ease of repair can pay off in many ways, building reputations and customer ‘stickiness’ (which reduces marketing and acquisition costs), creating opportunities for profitable new services that provide maintenance, spare parts and supporting resale.

Durable products can have multiple cycles of use, creating value for both the business and its customer. We can rethink the value potential of each unit of production: rather than ‘sell and forget’, banking the revenue from the initial sale and hoping that the profits will more than pay for customer service, marketing, new product development and other overheads, businesses can treat each unit produced as an asset, with potential to generate profit over and over again.

Let’s imagine a typical IKEA sofa, selling for €600. Making it easy to disassemble means it could come back to an IKEA store and be resold, for around €300. Another cycle of use might require a new cover, at €160, then a refurbishment gives the sofa another life, earning a further €100 for IKEA. Finally, by taking back the end-of-life sofa, IKEA could earn €10 for recycling. The sofa has now had four cycles of use, earning almost double the revenue, with substantial extra profits, and several happy customers with a good quality, affordable sofa. Everyone is doing better, with less.

Keeping your existing customers happy saves on marketing costs, too. Research says that acquiring a new customer is anywhere from five to 25 times more expensive than retaining an existing one. It makes sense: you don’t have to spend time and resources going out and finding a new client — you just have to delight the ones you already have.

Things can only get better!

We’ve heard from designers, disruptors and legislators – it’s clear that the business landscape is changing. Priorities are changing, and people are rejecting consumerism. They want less stuff, and want things to be affordable, accessible, and socially, ethically and environmentally acceptable

People are noticing that things don’t last as long as they should, and they are pushing back. Designers are also pushing back. They don’t want to be part of the problem, tasked with quality stripping and designing for disposability. They also want to be part of the solution.

Switched-on companies see durability and repairability as key to building trust in their brands, and to stay ahead of the emerging legislation around eco-design and Right to Repair. Longer-lasting products can have multiple cycles of use, creating more value for the company, its customers, workers and suppliers. Disappointed customers don’t return – and they tell their friends. Getting new customers is much more costly than keeping the ones you already have.

A new era is emerging, with designs that are resource-intelligent, not resource-intensive. Disruptors are tuning into what people want. They are re-learning the principles of democratic design and doing much more with much less: creating more value for people, planet and profitable business.

References

- GlobeScan Healthy and Sustainable Living Report 2023 (26 Oct 2023) GlobeScan Inc. Available from: https://globescan.com/2023/10/26/healthy-and-sustainable-living-report-2023/ [accessed 2 Apr 2024]

- The Green Divide: how to influence and change conscious consumer behaviour, Nielsen Consumer LLC (2023), p9. Available from: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/report/2023/how-to-turn-green-consumer-intentions-into-sustainable-actions/#report [Accessed 15 Mar 2024] and Global Consumer Archetypes to Foster Sustainable Living, Consumers International and GlobeScan (Dec 2023). Available from: https://www.consumersinternational.org/news-resources/news/releases/new-report-unlocking-sustainable-living-through-global-consumer-insights/ [accessed 6 Apr 2024]

- Global Sustainability Study: What Role do Consumers Play in a Sustainable Future? (2021) Simon-Kucher https://www.simon-kucher.com/en/blog/global-sustainability-study-what-role-do-consumers-play-sustainable-future

- Ingka Group (IKEA) report: people are taking more climate action but feel it’s not enough, 23 November 2023 (refers to IKEA & Globescan, People and Planet: Consumer Insights and Trends 2023). Available from: https://www.ingka.com/newsroom/ingka-group-ikea-report-people-are-taking-more-climate-action-but-feel-its-not-enough/ [accessed 2 Apr 2024]

- IKEA Circular Product Design Guide (2019) https://about.ikea.com/en/newsroom/2021/09/01/ikea-circular-open-source-blueprint

- Dieter Rams, Wikipedia, available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieter_Rams [accessed 12 Jul 2022]

- Helen Barrett, A new design democracy, FT Weekend (13-14 April 2024). Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/cab88856-f98f-4332-bd44-e1d2ba762265 [subscription only]

- European Parliament, EPRS Briefing, Consumers and repair of products (Sep 2019) Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/640158/EPRS_BRI(2019)640158_EN.pdf

- Planned obsolescence: Exploring the issue, Briefing 02-05-2016, European Parliament Think Tank, Think Tank. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2016)581999

- Thysen T, Berwald A, Consumers’ experiences with premature obsolescence – Insights

- from seven EU countries, Product Lifetimes and the environment (PLATE) 4th PLATE 2021 Virtual Conference (2021) https://doi.org/10.31880/10344/10186

- Circular Economy Podcast #128 Tara Button: products that say ‘Buy Me Once’ https://www.rethinkglobal.info/128-tara-button-products-that-say-buy-me-once/

- Tara Button, A Life Less Throwaway: The Lost Art of Buying for Life, Harper Collins (2018) https://tarabutton.co.uk/alifelessthrowaway

- Helen Barrett, A new design democracy, FT Weekend (13-14 April 2024). Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/cab88856-f98f-4332-bd44-e1d2ba762265 [subscription only]

- Harvard Professor Michael Norton’s 2011 research with Dan Ariely and Daniel Mochon on the ‘IKEA effect’: that if you build it, you love it more. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IKEA_effect

- Global Consumer Trends 2030, Mintel (updated April 2020) Available from: mintel.com/global-consumer-trends-2030 [accessed 10 Aug 2022]

International speaker, author and strategic advisor, Catherine Weetman helps people discover why circular, regenerative and fair solutions are better for people, planet – and prosperity.

Catherine’s award-winning A Circular Economy Handbook, published by Kogan Page, is now in its 2nd edition. Catherine also hosts the popular Circular Economy Podcast, with listeners in over 150 countries.

Catherine’s wide-ranging experience, systems-thinking perspective, and willingness to challenge business-as-usual, together with a deep understanding of circular and regenerative practices across industry sectors, means she’s uniquely qualified to help you succeed with circular. Read more about Catherine here.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or stay in touch to get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…