Will fast fashion survive the coronavirus lockdown? Big brands are cancelling orders and treating their suppliers as disposable. The time is right for slow, sustainable and circular fashion. We go behind the scenes to look at how the Baukjen and Isabella Oliver brands take a different approach, with beautiful, timeless designs and ethical, more sustainable production. We examine the brands’ circular and partnership approaches through the lens of Permaculture.

9 minute read

We are seeing, with fresh eyes, the interconnected nature of our economies – with their global supply-chains and the inextricable link between supply and demand. If shops aren’t open, and people are encouraged to avoid purchasing non-necessities, then sales fall off a cliff-edge, almost overnight. If people can’t work – because they are ill, self-isolating, or the work is ‘non-essential’, then nothing is produced and distributed. Even if your business operations are still running, the odds are that some part of your supply chain, upstream or downstream, comes to a juddering stop.

How long will this continue? Which businesses are resilient enough to survive? Zoe Wood, writing in The Guardian, highlights the bleak picture painted by reports from McKinsey and the Business of Fashion (BoF). Predictions show global fashion sales falling by up to 30 per cent in 2020. McKinsey predicts that if stores stay closed for two months, ‘80 per cent of listed fashion companies in Europe and North America will be in financial distress’.

Disposable products, people and partnerships

Fashion giants are already cancelling orders at scale, threatening the survival of hundreds of low-cost suppliers. Those big corporates have built their business models on cheap supplies from Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and other developing countries. This was highlighted by another article in the Guardian, reporting an estimate from the Workers Rights Consortium, that over £20 billion of orders may have been cancelled. Those orders will include clothes already made. Small suppliers will be bankrupt, and workers will lose their jobs. As the article points out, many lower-income countries ‘will struggle to provide economic safety nets for millions of low-paid workers’.

Many of us are shocked by this lack of compassion, resilience, and humanity. Big companies have decided suppliers and workers are dispensable. Fast fashion exists to take, make and dispose. We are realising this applies not just to its products – but to the people and partners in the business.

How will fast fashion’s business model emerge from the lockdown? Will people start to question the appeal of fast fashion? Will they realise that it doesn’t matter? That instead, conversations, community and what difference we make are the truly important things in life? And that not being manipulated into consuming – ‘work, buy, consume, die’ – saves us money and time. Even better, it avoids that subconscious discomfort that you’re supporting exploitation, pollution, destruction – and profits for the already super-rich.

A sense of purpose

“One of the most robust findings in the happiness literature is the centrality of productive human endeavour in creating a sense of purpose in life… What makes work meaningful is not the kind of work it is, but the sense it gives you that you are earning your success and serving others.” Arthur C. Brooks, How to Build a Life

People everywhere are searching for purpose and meaning. They want their choices to count. Forbes Magazine highlighted Accenture Strategy’s 2018 Global Consumer Pulse Research. It revealed that consumers, across all generations, care about what retailers say and how they act. Rachel Barton, managing director at Accenture Strategy said “Consumers have the power to bring about success or failure to companies. They are more than buyers – they are active stakeholders and want to feel a sense of shared purpose,” warning that “If retailers don’t react, they now face consequences.“

The survey found that more than half (53 per cent) of consumers who are disappointed by a brand’s words or actions on a social issue complain about it. The younger generation goes further, with over half of Gen Z and millennial consumers saying they were likely to boycott brands that don’t reflect their values and beliefs.

As Barton says “Why settle for anything less than a brand that has integrity, respects the environment that it operates in, treats its people fairly and respects the world that they live in?”

The Accenture report quotes Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock, Inc.

“The public expectations of your company have never been greater… Every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Without a sense of purpose, no company, either public or private, can achieve its full potential.”

Are those luxury fashion brands switching to making masks and ‘scrubs’ discovering the ‘power of purpose’? Call me cynical, but I suspect most of them are not.

So what’s the alternative? How can those brands with a purpose beyond profit compete against this ‘sell more’ approach?

Slow, sustainable and circular

In episode 25 of the Circular Economy Podcast, I interviewed Geoff van Sonsbeeck. Geoff is the Co-Founder and CEO behind the direct to consumer womenswear brands BAUKJEN and ISABELLA OLIVER, and has been at the forefront of the slow, sustainable fashion movement for over 15 years. Baukjen focuses on environmentally, ethically and socially conscious style for a sustainable future. It is working through the process of certification as a B Corp.

Geoff explained how the two brands are building on their durable and timeless design ethos and are now evolving a range of circular practices.

When reflecting on the value that Baukjen and Isabella Oliver provides to their various stakeholders – customers, suppliers and partners, employees, shareholders – the word ‘care’ kept cropping up. What do I mean by ‘care’? Let me unpack that a bit, by looking at Baukjen cares for its different stakeholders.

- As a customer, I get well-designed and well-made clothes, with flattering shapes and beautiful fabrics. The garments are easy to care for and last for many, many wears. It is clothing that makes me feel good and look stylish.

- As a supplier, making those long-lasting designs means I can invest in equipment, facilities, training and technology, and feel secure about our company’s future. I feel confident that we’ll get repeat orders for the same style. That means I don’t worry about whether the next ‘fashion hype’ design will sell. I feel like a partner, rather than a supplier. I’m more likely to share my ideas for how our partnership could evolve, ways to improve the design, the fabrics, new circular approaches and so on.

- As an employee, being involved in making those long-lasting and high-quality designs encourages me (and gives me time) to build my skills. Those high-quality designs often include elements that need high-level design and production techniques, which means I can build my skills and enhance my career prospects. I want to invest my time and future in this company.

- As a shareholder, I feel good about my investment. I can see that the company provides what the other stakeholders need – from beautiful clothing to rewarding relationships – and that the company is treating them all as partners.

People can see how the company cares for them, by providing high-quality products and being a sound investment for the future. The elements of care go beyond those people directly involved.

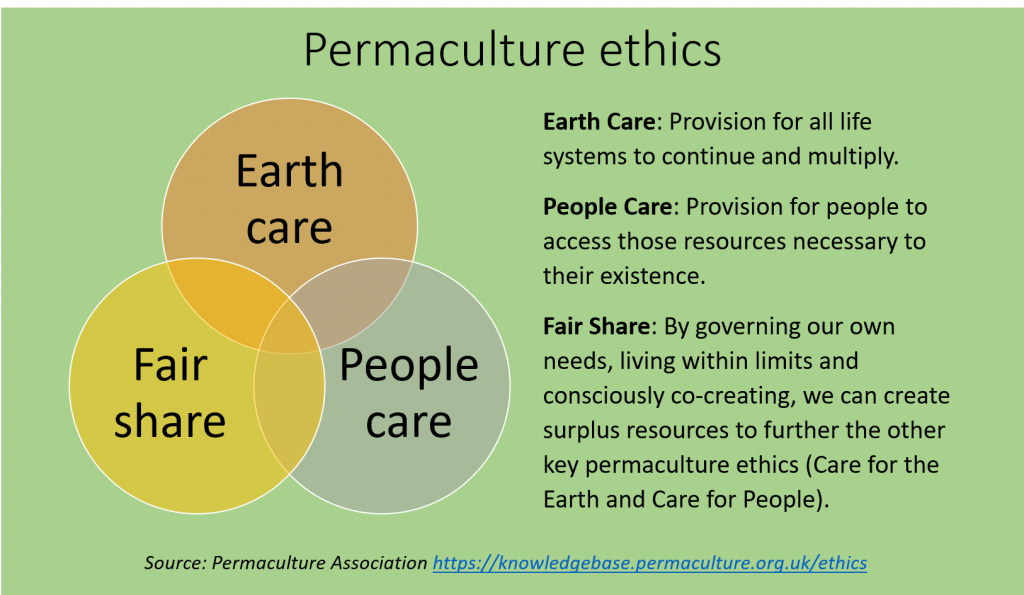

Permaculture ethics

Back in 2014, I did a Permaculture Design Certificate. Permaculture is a creative, and ecologically sound approach to providing for our needs and tread more lightly on the earth. Permaculture Magazine describes it as:

- An innovative framework for creating sustainable ways of living

- A practical method of developing ecologically harmonious, efficient and productive systems that can be used by anyone, anywhere.

Permaculture was developed in the 1970s, ahead of the circular economy. If you’ve already come across Permaculture, you’ll be familiar with its three ethics: earth care, people care and fair share.

- Earth Care: Provision for all life systems to continue and multiply.

- People Care: Provision for people to access those resources necessary to their existence.

- Fair Share: By governing our own needs, living within limits and consciously co-creating, we can create surplus resources to further the other key permaculture ethics (Care for the Earth and Care for People).

You can find out more about Permaculture and these ethics on the Permaculture UK Knowledgebase.

Sustainable fabrics

For Baukjen, Earth Care means choosing more sustainable fabrics, together with reducing waste and pollution. The current range of fabrics with a lighter footprint includes viscose and lyocell, plus ethically-sourced merino. In the podcast, Geoff Van Sonsbeeck mentions two fabrics, Ecosphere and Tencel. Baukjen is moving away from organic cotton, instead choosing more sustainable alternatives.

Similarly, outdoor gear brand Patagonia is securing its resources and reducing its footprint by swapping from high-impact and water-dependent cotton to bast fibres like hemp. In Let My People Go Surfing, Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia’s founder, explains the background to the company’s commitment to organic and regenerative cotton.

In 1988, after opening a new store in Boston and stocking the shelves with lots of cotton sportswear, Patagonia employees were complaining of headaches. Patagonia closed the store and investigated – a chemical engineer found the employees were breathing in formaldehyde fumes.

Patagonia started asking questions, finding that most ‘100 per cent pure cotton’ clothing is typically only 73 per cent cotton. In other words, over a quarter of the fabric consisted of chemicals, including formaldehyde (a toxin), applied to stop wrinkling and shrinkage.

Patagonia says: “When we scrutinized fabric fibres to determine their environmental impact, we figured cotton was ‘pure’ and ‘natural’, made from a plant. We were right about the plant. As it happens, very little is pure or natural about cotton when it is raised conventionally.”

Reducing waste and pollution

Baukjen reduces waste through a range of approaches. Firstly, as we’ve seen, it produces durable, high-quality designs that focus on flattering shapes and timeless colours. That means customers can create ‘capsule’ wardrobes, instead of finding they’ve bought an ‘on-trend’ top that clashes with their existing clothes.

As people keep those garments for much longer, this reduces the quantities of end-of-use clothes they discard when making room for new clothes. What’s more, the ‘cost per wear’ is much lower, offsetting or outweighing the cost of the higher-quality garments.

In addition, Baukjen focuses on supply-chain waste, planning ‘little and often’ production runs to avoid overstocks and stock write-offs.

ShareCloth, an ‘on-demand retail and manufacturing solution’, has published a comprehensive summary of the overproduction issues: The 2018 Apparel Industry Overproduction Report and Infographic.

The report includes some jaw-dropping statistics. One source estimates that 30% of clothes are never sold (a similar statistic is in this 2016 Ecotextile News article. What’s more, a big proportion of clothes are sold at a discount – NPD Group estimates 75 per cent (presumably in the US).

Baukjen now encourages customers to return their end-of-use clothing (with pre-paid postage). Baukjen aims to give those clothes another life, by reselling them in its Pre-Loved collection or distributing them to its charity partners for reuse. Failing that, the clothes are recycled.

This service covers both its Isabella Oliver brand and maternity wear made by its competitors too. However, the lower quality of much of the competitor’s clothing means that recycling may be the only practical option to keep the resources in the system for another use-cycle.

People care

We’ve already explored the wellbeing and ‘meaning’ benefits for customers and employees, and there are more. For Baukjen, care of people goes beyond the product design. Baukjen vets its factories, selecting only those that support the environmental, ethical and social needs of the people working there.

The choice of fabrics, chemicals for dyes and finishes, and the processes are all under the spotlight. Reducing chemical use improves worker safety, and avoiding pollution is better for the community living around the factory. Many of us will have seen photos of people washing their clothes and pots in heavily polluted water around textile factories.

Reducing production, supply chain and end-of-use waste leads to fewer garments end up in landfill or incineration. That, in turn, reduces pollution, ecosystem degradation and adverse impacts on human health.

Earth care

It’s easy to see that many of these benefits flow through to the Earth Care ethic too. By avoiding pesticide- and water-hungry crops like cotton (around 2,700 litres of water just for a t-shirt) and fossil-based fibres like polyester, nylon and acrylic, Baukjen helps minimise pollution and ecosystem destruction. For example, digital printing significantly reduces ink consumption, water pollution and energy usage.

Avoiding deforestation and taking care to source ethically-produced animal products helps to support sustainable and regenerative agriculture. Bauken’s ethical approach includes ‘mulesing-free’ wool and ‘by-product leather’

Fair share

Baukjen is committed to ethical standards, both for its in-house operations and those of its suppliers. Factories sign up to a code of conduct, which includes living wages, safe conditions, regulated working hours and forbids child labour. This ensures a fair exchange between the supplier and its employees.

Building a trusted brand

We can see how Baukjen’s values and ethics builds trust for all its stakeholders. Those stakeholders are supporting a brand with values that align with their own. They trust that it is doing the right thing and is continually raising the bar. They will support the next promise Baukjen can make, to do more good and create a better world.

This, in turn, creates a sense of pride. From the factory apprentices to the product designers, from the warehouse operatives to the finance team, from customers to communities close to the operations – everyone can feel proud of their involvement, with positive stories to tell their family and friends.

- Engaged employees work harder, and are less likely to leave.

- Engaged suppliers behave like partners, sharing their good ideas for improvement and investing in future projects.

- Engaged communities want that business to succeed and will encourage locals to work there and become customers.

- Engaged customers will tell their friends how brilliant you are, and bookmark your website instead of browsing for something else.

- Even better, word-of-mouth marketing is more powerful (and costs less!) than ‘influencers’ pay-per-click, discounts and promotions.

According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, fashion is ‘the prevailing style (as in dress) during a particular time’. My prediction is that future-fit fashion will be slow, savoured and sustainable, instead of fast and forgettable.

What do you think?

Related posts:

- 7 reasons why the circular economy is better for your business

- The best circular strategy is NOT recycling

- Why reuse is #1 tool in the circular economy toolkit

- The ‘new normal’ – why renting clothes is better for us, our planet, and our babies

- Worried about supply-chain disruption? Why circular economy approaches are more resilient

Catherine Weetman advises businesses, gives workshops & talks, and writes about the circular economy. Her award-winning Circular Economy Handbook explains the concept and practicalities, in plain English. It includes lots of real examples and tips on getting started.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or find out more about Catherine’s award-winning book: A Circular Economy Handbook for Business and Supply Chains.

Why not stay in touch and get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…