7 minute read

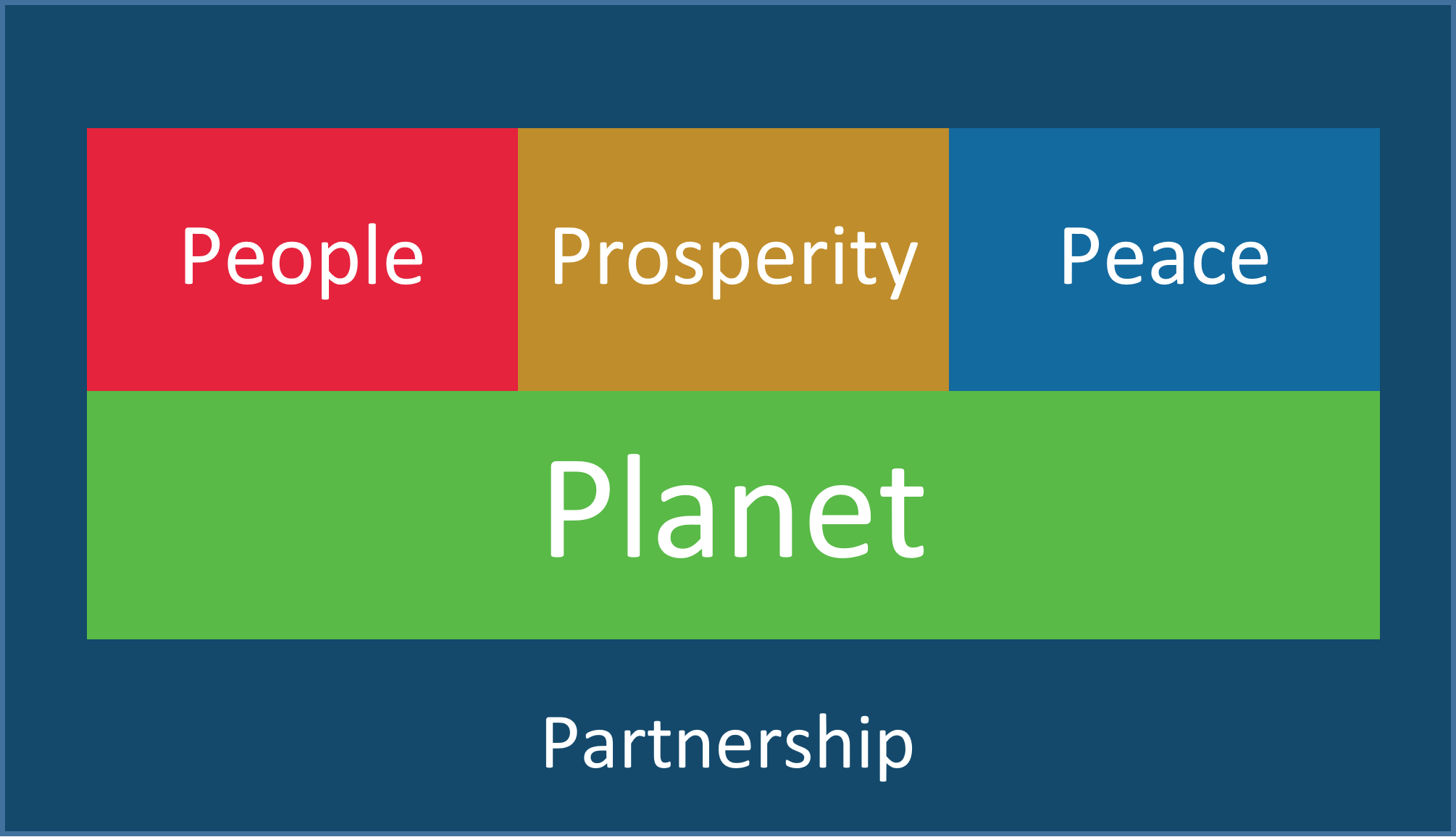

Those of us interested in sustainability and the circular economy are acutely aware of the multiple challenges facing our society, including climate chaos, ecological destruction, poor health, poverty and worsening inequality.

We know the circular economy aims to reduce, reuse, remake and eventually to recycle – the four ‘Rs’ of the loops. But what if there is another R – rebound – opening the door for companies to adopt circular strategies and still drive growth in consumption (and pollution and waste)?

Urgent challenges

The most recent update of the Planetary Boundaries framework concluded that ‘society’s activities have pushed climate change, biodiversity loss, shifts in nutrient cycles (nitrogen and phosphorus), and land use beyond the boundaries into unprecedented territory’.

At the same time, rising inequality and poverty are causing hardship, leading to unrest and riots around the world. Back in August, Bloomberg reported that ‘More than 30 of the world’s biggest companies signed on to an effort to spread the benefits of economic growth, saying that rising inequality is the ‘defining challenge of our time.’ The initiative, sponsored by the OECD, saw companies pledging to support ‘inclusive growth.’ Examples include agreeing to principles such as respect of freedom of association for labour and supporting projects such as increasing affordable housing to financing small business.

Meanwhile, in the US, some Democrats are campaigning on a ticket for a Green New Deal, and there is plenty of discussion on the need for degrowth. Both have their fans, and detractors – with some seeing them as a left-wing attack on the capitalist model, and others arguing that degrowth is just another form of ‘austerity’ and will worsen inequality and poverty.

From Limits to Growth to Degrowth

According to Wikipedia (not an accredited source, according to my publisher!), the Degrowth movement emerged after the Limits to Growth report to the Club of Rome (in the 1970s). It included contributions from some of the earliest circular economy and systems-thinkers).

Degrowth thinkers and activists argue that overconsumption lies at the root of our systemic environmental issues and social inequalities. Instead, they believe we should reduce levels of consumption (and production), aiming to maximise well-being through ‘sharing work, consuming less, while devoting more time to art, music, family, nature, culture and community’.

The Degrowth academic association acknowledges the difficulties of getting people to rally around a single strategic vision. They say: ‘The multi-level nature of our complex societies obliges the degrowth movement to follow multiple strategies. This has led to a plethora of engaged debates.’

Perhaps degrowth just needs re-branding. Kate Raworth (of Doughnut Economics fame) thinks so, in this article from 2015.

What does the Circular Economy promise?

From the Limits of Growth came those early thinkers on circular solutions, especially Walter Stahel and Gunter Pauli. They envisage an economy that can conserve nature and regenerate living systems, provide meaningful jobs and encourage ‘use’, instead of ‘consumption’.

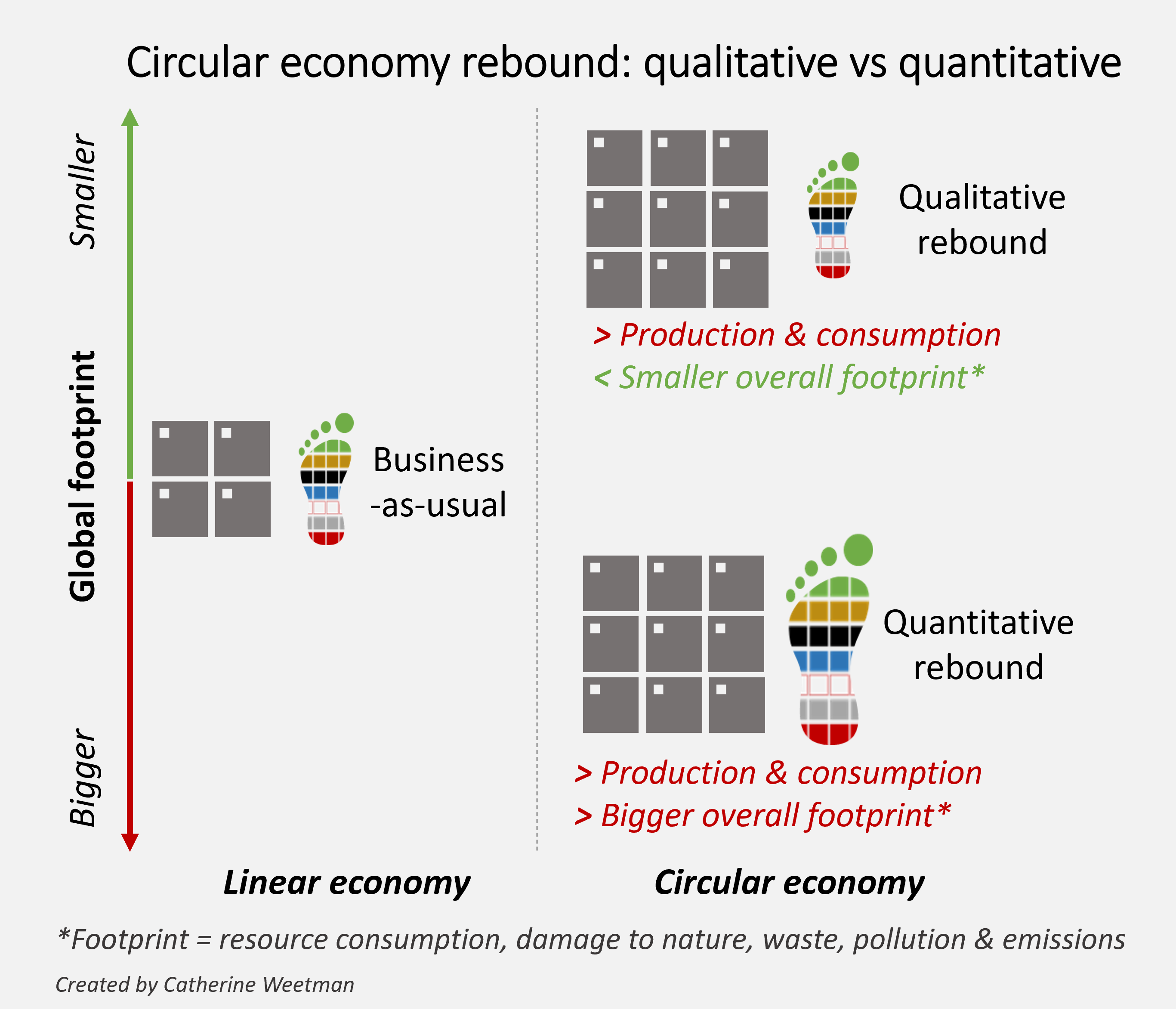

Yet Trevor Zink and Roland Geyer, in their influential research paper on ‘Circular Economy Rebound’, highlight the dangers of strategies that result in an increase in net environmental impact, resulting in ‘circular economy backfire’, ie rebound. They point out that circular economy schools of thought tend to split into three camps:

- those focusing on minimising resource extraction and waste

- consultancies and businesses, prioritising opportunities for economic (revenue) growth

- Industrial Ecologists and others, who focus on reducing adverse environmental impacts.

Some people feel the circular economy is being undermined, with consultancies and businesses ‘cherry-picking’ circular approaches to reduce costs, improve customer lock-in and enhance brand reputations. Crucially, some of these approaches can maintain or even encourage more consumption.

So what is ‘rebound’?

Helpfully, Mike Berners-Lee’s recent book ‘There is No Planet B’ explains the rebound effect, using the example of buying a more efficient (eg electric) car. It saves fuel and carbon emissions, but those savings might be lost in a number of ways:

- you drive further each year;

- you can afford to live further away from work in a larger property that needs more heating;

- fuel stations adjust to the drop in demand, lower their prices and sell more to others;

- you spend the fuel savings on other things that have a higher carbon footprint;

- car manufacturers change their marketing approach to sell their less efficient cars to others;

- the oil industry adjusts its strategy to sell to other industries and countries;

- and so on.

In addition to the electric car example above, we have those ride-hailing apps that increase car miles by luring people away from walking, cycling and public transport.

Why might rebound undermine the circular economy?

Drawing parallels with energy-efficiency rebound, Zink and Geyer argue that repair, refurbishment and similar approaches are likely to increase overall production, because they reduce the cost of the second-life product. Their examples include refurbished cellphones and recoverable rocketry (space exploration equipment, as pioneered by SpaceX and Virgin Galactic).

In addition, they highlight potential the downsides of switching from physical goods to ‘virtual’ services (eg video on demand instead of a video player and DVDs). This might result in high levels of streaming and downloads, all requiring energy for data transfer, storage and viewing.

To avoid rebound, they argue that the circular economy must actually draw the user away from primary production [and resource extraction] so that ‘secondary goods’ must actually substitute for primary goods. [NB ‘primary production’ means the initial production of the brand-new product, whereas ‘secondary production’ is some form of refurbishment, remanufacturing and so on.] They warn that this is a ‘substantial hurdle given that the two primary tools that a marketer might use to draw away customers—lowering prices or finding niche markets—are off-limits in order for the circular economy to avoid rebound.’

High-quality and durable vs cheap and disposable

However, I’m not sure those arguments about repair and refurbishment hold true. Repair and refurbishment (and remanufacture) were happening before the circular economy was conceived. If there is a market to address, companies will find a way to meet market needs. In other words, if people want smartphones but can’t afford the top brands, that opens up a market for a cheaper phone, with most of the functionality of the best-in-class models.

Let’s explore that cellphone example. Rapid advances in technology mean the cost of producing cellphones quickly becomes cheaper. That means companies can make them even more affordable by using cheaper, less durable materials; cheap construction methods like bonding and glueing instead of removable fixings; and avoiding the expense of providing repair instructions, repair facilities or spare parts.

Surely a better solution is a high-quality, durable phone that can be repaired, remanufactured and upgraded, and is designed for disassembly and recovery of value at the end-of-life. That offers many benefits over a cheap, disposable phone: for the phone user, for society and the environment – and for the company making the circular economy cellphone.

How do we avoid rebound and reduce consumption (& waste)?

Researchers John Mulrow and Victoria Santos note that many of the journal authors raise the issues of rebound effects and the failure of recycling initiatives to reduce material extraction and its impacts. Summarising a special edition of the Journal of Industrial Ecology, ‘Exploring the Circular Economy‘, they cite research from Nancy Bocken and her colleagues:

‘The basic premises of the CE appear to be closing and slowing loops. Closing loops refers to (postconsumer waste) recycling, slowing is about retention of the product value through maintenance, repair and refurbishment, and remanufacturing, and narrowing loops is about efficiency improvements, a notion that already is commonplace in the linear economy.’

Reflecting on the collected observations of the journal authors, Mulrow and Santos suggest that we should add shrinking loops to the list of circular economy premises. They highlight the importance of social aspects for solutions like reuse, refurbishment and durability, and note the strong rebound effects of ‘virtualization’ – providing digital services to replace physical activities. They conclude that industrial ecology experts show ‘there are two major gaps in the Circular Economy’s relevance for achieving global sustainability. It has not developed language or methods, or necessarily acknowledgement, of the need to shrink and slow material throughput.’

What other criticisms are emerging?

Unfortunately, the ‘rebound’ effect reminds us that circular is not necessarily sustainable and better for society. Companies can make use of circular approaches and yet still be putting toxic chemicals or unrecyclable materials into the market. They can design a perfect circular product, and still be exploiting workers along the supply chain. They can be making recyclable products with very little chance of those products will be recovered and recycled.

In the last newsletter, I shared an article from the Resilience website, with John Mulrow (again) and Erik Assadourian making the case for a ‘marriage between degrowth and the circular economy’. They argue that shrinking our demand for both materials and energy is essential if we are to have an economy that functions within the earth’s limits. They worry, like Zink and Geyer, that some consultancies and businesses, and even governments, see the circular economy as a way of continuing to fuel growth, by avoiding the constraints of finite resources.

Most importantly, Assadourian and Mulrow argue the need for a circular economy with a much smaller throughput, ‘spiralling down’ as we get better at recirculating and using fewer products and materials together with less water and energy – a ‘Spiral Economy’. Their article includes other suggestions for how to achieve this aim of ‘one planet living’, where we regenerate land, water, resources and ecosystems and can thrive and prosper within the means of our planet.

Degrowth – or regeneration?

Let’s get to the point – can the circular economy help solve our ‘take, make, waste’ problems? Or are unintended consequences leading to rebound, and driving even more consumption and destruction? Critics of the circular economy are concerned that it is being deployed to drive growth and potentially increasing consumption – not ‘bending the curve’ on our exponential growth in resource use, land-use change, emissions and more.

Remember, we are using up resources much faster than they can be regenerated. Circle Economy calculates our world is only 9 per cent circular, and the Footprint Network estimates our global ecological footprint at 1.6 planets. Our global issues of extraction, pollution and waste, leading to damaged ecosystems, degraded land and contaminated water, plus the critical issues of Greenhouse Gas levels and air pollution, mean we need to go further (fast). We urgently need to design systems, legislation and business models for an economy that restores resources, natural systems – and society.

The bottom line

It feels as though regeneration is lacking attention, even though we know that being sustainable and closing the loop on materials is not enough. We need to ‘raise the bar’ even higher, aiming for regenerative models that restore our damaged ecosystems, clean up pollution and waste and restore health, wellbeing and prosperity to society.

At the same time, business needs to be profitable, so it can invest in development and regeneration. But it doesn’t necessarily need to grow – though if a regenerative business grows at the expense of a linear, destructive business, that seems like a good outcome.

The bottom line is this… we need a circular economy that manages, preserves and regenerates resources, working within the earth’s limits to support a healthy, prosperous society. A circular, regenerative business means resilience, profitability and sustainability: a better business, and a better world.

Catherine Weetman advises businesses, gives workshops & talks, and writes about the circular economy. Her award-winning Circular Economy Handbook explains the concept and practicalities, in plain English. It includes lots of real examples and tips on getting started.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or stay in touch to get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…