Unpacking the tricky topic of ‘circular economy rebound’: when circular solutions end up causing more production and consumption, not less. Is it always a problem? We define rebound, look at examples of rebound for clothing, mobility, and smartphones, and ask whether some types of circular economy rebound are still better for people and planet.

10 minute read

In the first article in this 2-part series, I advocated for the circular economy as the best tool available to design new systems, that help conserve and regenerate materials, ecosystems, and communities.

But there are some big caveats. If we look closely, we can see some circular approaches that are beset with unforeseen and even negative consequences. To put it bluntly, there are ways of ‘going circular’ that don’t improve sustainability and can even have negative impacts.

In this second part, I promised to unpick the tricky topic of ‘circular economy rebound’: when circular solutions, instead of reducing production and consumption, end up increasing it.

In part one, I examined the root causes of the ‘wicked’, interconnected, and complex problems at the heart of our sustainability crises, including our ever-growing resource and pollution footprint and our belief that economic growth makes the world a better place.

Then we moved onto examine what I’ve called ‘false solutions’ – interventions and innovations that are circular, but don’t create more sustainable solutions.

Often, they solve one problem but create others. Crucially, they don’t help to shrink our footprint – resource use, waste, pollution, and destruction of nature.

So what is rebound?

You may have come across the term, ‘rebound’ (also known as Jevons’ Paradox*), especially in the context of energy. In a broader sense, it means that making things more convenient, efficient, or cheaper, can encourage us to use or consume more of them. So instead of shrinking our footprint – materials, carbon, waste, and destruction of nature – we increase it.

*The ‘rebound effect’ was first described by William Stanley Jevons in his 1865 book The Coal Question, in relation to more efficient steam technology.

Let’s unpack that. In explaining rebound in the 2nd edition of A Circular Economy Handbook, I used a helpful example from Mike Berners-Lee’s book, ‘There is No Planet B’. He asks us to think about buying a more efficient (eg electric) car. It saves fuel and carbon emissions, but those savings might be lost in several ways:

- you drive further each year

- you can afford to live further away from work in a larger property that needs more heating

- you spend the fuel savings on other things that have a higher carbon footprint

- fuel stations adjust to the drop in demand, lower their prices and sell more to others

- car manufacturers change their marketing approach to sell their less efficient cars to others

- the oil industry adjusts its strategy to sell to other industries and countries, and so on.

So how does rebound relate to the circular economy?

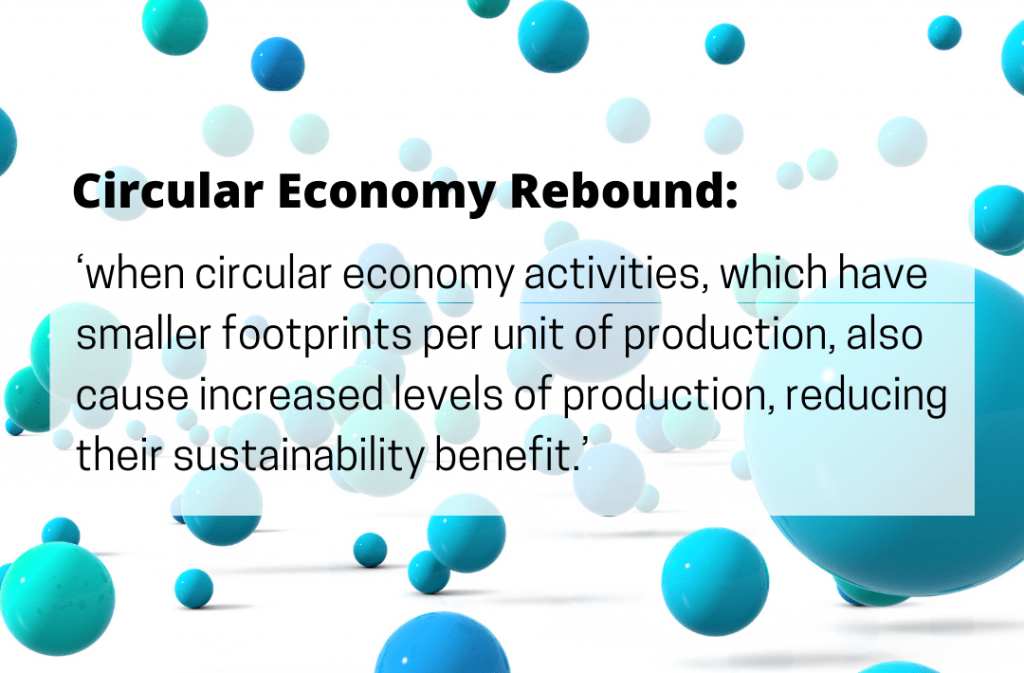

Over the last few years, several studies have drawn attention to the risks of rebound when circular economy approaches make something more easily available or affordable. Trevor Zink and Roland Geyer, in their 2017 article, define Circular Economy Rebound as occurring ‘when circular economy activities, which have lower per-unit-production impacts, also cause increased levels of production, reducing their benefit.’

As I noted in my 2019 article on circular economy rebound, Zink and Geyer argue that circular approaches including repair, refurbishment and even recycling are likely to increase overall production, because they reduce the cost of the second-life product. Their examples include refurbished cellphones (smartphones) and ‘recoverable rocketry’ (space exploration equipment, as pioneered by SpaceX and Virgin Galactic).

Zink and Geyer also highlight the potential downsides of ‘virtualising’ – switching from physical goods to ‘virtual’ services, such as streaming music from the internet, instead of using a CD player and buying CDs. That seems a valid concern, and one that could be easily underestimated. We’re starting to see reports that high levels of streaming and downloads use significant amounts of energy for data transfer, storage and listening/viewing – though Carbon Brief notes that many reports exaggerate the effects.

Let’s think about some other examples, for mobility, furniture, and clothes.

The hidden costs of ride-hailing

A report a few years ago found that after ride hailing apps like Uber and Lyft started up in US cities, the result was an increase in overall car miles within the city. The apps’ flexible-pricing models can undercut the price of public transport, potentially making ride-hailing so cheap that people give up walking and using their bikes. We might suspect the apps are using below-cost pricing to draw in users, hoping to cultivate a ride-hailing habit over the longer term.

How can the apps afford to charge less than the costs of the driver, car, fuel etc? Often, these companies have investors with deep pockets, and a desire to monopolise the market in their target regions. Once the ride-hailing platforms have critical mass, they can put the prices back up.

What are the hidden costs? Increasing car use and switching from ‘green’ travel options makes cities more congested. Plus, we know that car travel creates emissions, pollutants and particulates which harm human health, as well as being bad for our planet. And there are other issues: it’s worth remembering that many of these companies are part of the ‘gig economy’, and they’ve been accused of exploiting their drivers. So again, that’s taking us in the wrong direction – it’s not shrinking our footprint or improving lives.

Bring-back schemes: supporting resale, or increasing sales?

More big businesses are showing signs of adopting circular economy models. IKEA says it wants to be a circular, regenerative business, and IKEA’s CEO Jesper Brodin says that having circularity in your model is key to staying affordable, creating products that that everybody can buy.

In 2020, IKEA trialled a buyback scheme in 27 countries as part of its ‘Black Friday’ promotion, giving people vouchers for bringing back their unwanted IKEA furniture. Apparently, the trial went well, and IKEA is rolling the scheme out as an extended pilot in several countries.

We could see this as evidence of IKEA’s move towards a circular, regenerative business model. It can be a sensible trial, to understand what kinds of things people want to bring back, what condition they’re in – and whether IKEA can resell those products – do they have resale value or are they too damaged?

If they’re not fit for resale, this could help IKEA understand how best to recycle them. Even better, it should help IKEA decide what design changes are needed to create products that are more durable, repairable, and recyclable.

But on the other hand, we could see it as another example of potential rebound – offering vouchers encourages people to come back to the store, offload their old furniture and buy more stuff. Having returned something might also reduce the ‘guilt’ of their next purchase.

What about clothing?

Earlier in 2021, a research paper generated headlines, with The Guardian, Fast Company, The Times and many others concluding that renting fashion was the worst option for the planet.

The study in Environmental Research Letters, by researchers in Finland, seemed rather narrow. Focusing only on jeans, it compared several circular options, modelling scenarios involving wearing the jeans 200 times. For the rental option, the jeans were swapped for a new pair after being worn 10 times, and a car was used to travel 2km to the rental point. Does that feel like a typical scenario?

It’s also worth noting that the study compared ‘Global Warming Potential’ factors – so it excludes analysis of materials, process chemicals, water use, and all the other pollution and ecosystem damage along the process and from the end-of-use waste. Not surprisingly, the rental option has a bigger carbon footprint compared to keeping the jeans for 200 wears.

Like me, you can probably envisage scenarios where renting clothes could be a lower footprint option, compared to buying. Babies and children grow out of each set of clothes within a few months and so need regular replacements. Here, rental can be both convenient and good value – and it means the clothes can be checked, cleaned, repaired if necessary, and have several useful lives before they are worn out.

Without a rental option or having access to a sharing ‘system’ (formal or informal), the sustainable alternative involves hassle. You need to find ways to donate or resell the clothes, then replacing them with new or spending time trying to find suitable pre-used items.

Similarly, for more expensive clothes we might wear for a friend’s wedding or important occasion, it seems better to rent instead of buying and then reselling. What’s more, renting gets much more use out of the clothes than keeping something that might only be worn a few times. We can also encourage people to buy pre-used, and to donate or sell their unused clothes when they’re no longer in regular use – and many of us do that.

I think we need more studies for different types of products, looking at the pros and cons of various circular options. I’d love to see analysis highlighting the ‘break points’: at which point does each choice provide the lowest footprint? For example, how many times do I need to wear that sweater, to be sure that buying a new one was the best sustainable choice? And if I plan to buy something, how many times should I wear it to know that buying was better than renting or reselling?

Is resale better than renting?

These days, resale of clothes and other products is easier, whether through mass-market platforms like eBay, or category-specific sites like the mainstream clothing platform ThredUp or niche options like designer resale site Hardly Ever Worn It (HEWI).

But, as sustainable fashion consultant Deborah Campbell pointed out recently, problems can arise when brands use eye-catching statistics to suggest that second-hand purchases automatically displace new items, or that resale stops garments from being discarded. Do these claims help people feel they’ve reduced their footprint, when they’ve added an extra garment to their wardrobe (even though the pre-used option probably has a smaller adverse impact than the new alternative)?

Bouncing back to smartphones

It’s time to return to the question of smartphones. In explaining their view that circular interventions mean smartphone consumption will rebound, Zink and Geyer say, ‘displacement of new smartphones by refurbished ones is likely to be low given that refurbished phones are typically sold in developing countries where the alternative is no phone at all.’ In other words, they think many of the refurbished smartphones will be bought by people who wouldn’t be able to justify the cost of a new smartphone.

Let’s back up a bit, to think about what happens when new products or services are invented. If we track sales, we could chart a ‘diffusion curve’ – a graph showing the number of new users (buyers) against a timeline. There are slightly different theories about diffusion, but the basic premise is that the ‘innovators’ (those who are keen to buy new and innovative products) are the first to buy, and then, as more and more people become aware of the product, are attracted to its benefits, and decide to buy, sales increase.

Often, the product is much more expensive when first launched, becoming cheaper as demand grows and production scales up, or as competitors launch similar products with lower prices. A saturation point is reached once the maximum number of customers have adopted the given product or service.

It’s complicated!

I can see complex factors to consider in assessing whether rebound occurs. For example, was demand for this type of product increasing anyway? Even though the circular intervention improves affordability or accessibility, should we attribute all the increased take-up to circular economy rebound?

For objects that have become highly desirable (like a smartphone), then people may decide to buy a smartphone, even at a high price, by forgoing other non-essential spending. The lower cost of refurbished or subscription services can make the smartphone more affordable, but is it correct to assume people wouldn’t have bought a phone anyway, even without the circular option?

Diffusion versus displacement

I’d argue that circular interventions can accelerate something that would happen anyway.

We can envisage that over time, pretty much everyone who wants a smartphone would, at some point, be able to afford one. It’s likely that some smartphone take-up has happened earlier, but in the long term, it doesn’t necessarily increase the overall production footprint. (Of course, that depends on people not treating them as ‘fast fashion’ items, to be replaced within a year or so of purchase!).

We could see circular economy interventions as helping speed up product diffusion, with the benefit of a smaller footprint compared with making new products to meet demand. Reuse and refurbishment can use less resources and energy compared to new, and might displace production of cheaply made, poor quality alternatives that are likely to be designed, made, and sold to meet rising demand for affordable phones.

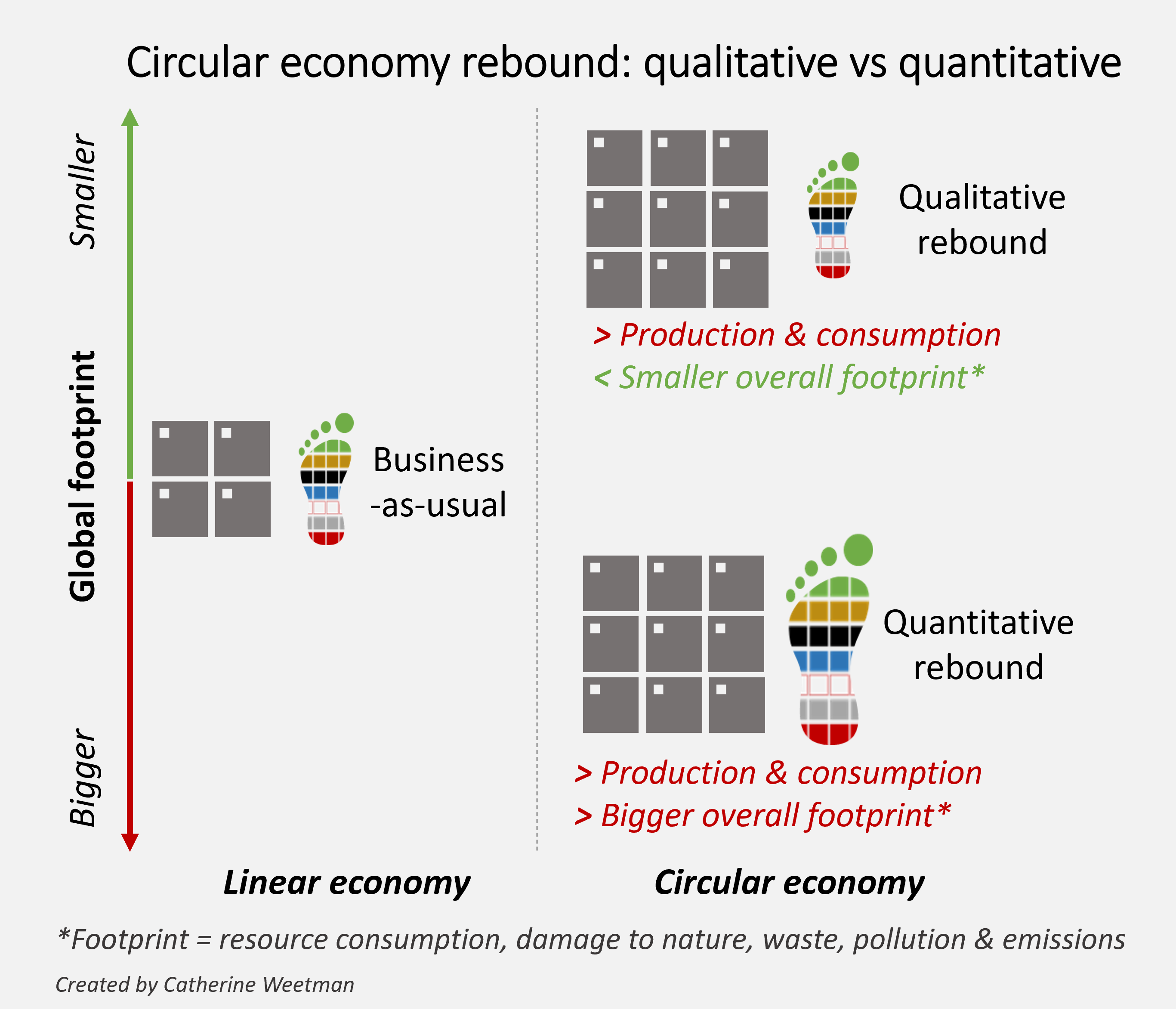

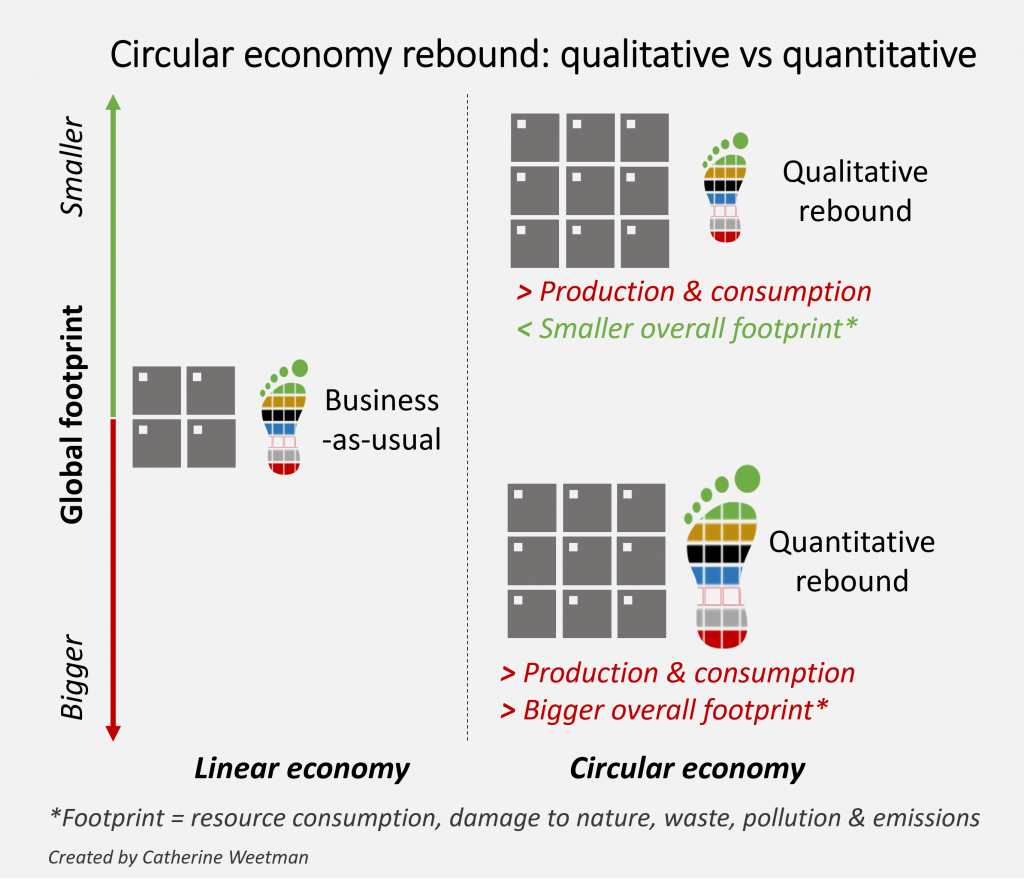

Bertrand Piccard, explorer, balloonist, and ‘inspioneer’, was the first to circumnavigate the globe in a solar powered plane in 2016. Interviewed on the Outrage and Optimism podcast, Piccard shared his thoughts on how sustainable business can be more profitable, and why we need Tao Economics. He senses we are in a fight between those aiming for degrowth (leading to social chaos) and unlimited growth (leading to ecological chaos), and believes there is a better, third choice – qualitative growth. “Qualitative growth is when you make money and create jobs by replacing what is polluting, by what is protecting the environment.”

So I’m suggesting we can have ‘qualitative rebound’: addressing social inequality and improving wellbeing. To improve social fairness and improving standards of living around the world, we might even seek out ‘levelling up rebound’ opportunities, where circular interventions would allow more people to access products or services that improve their health, security, or basic quality of life. The circular aspect may accelerate the change but does so in a way that reduces the overall footprint (resources, waste, and pollution) of the generic product.

Bertrand Piccard, explorer, balloonist, and ‘inspioneer’, was the first to circumnavigate the globe in a solar powered plane in 2016. Interviewed on the Outrage and Optimism podcast, Piccard shared his thoughts on how sustainable business can be more profitable, and why we need Tao Economics. He senses we are in a fight between those aiming for degrowth (leading to social chaos) and unlimited growth (leading to ecological chaos), and believes there is a better, third choice – qualitative growth. “Qualitative growth is when you make money and create jobs by replacing what is polluting, by what is protecting the environment.”

So I’m suggesting we can have ‘qualitative rebound’: addressing social inequality and improving wellbeing. To improve social fairness and improving standards of living around the world, we should aim for ‘qualitative rebound’ opportunities, where circular interventions would allow more people to access products or services that improve their health, security, or basic quality of life. The circular aspect may accelerate the change but does so in a way that reduces the overall footprint (resources, waste, and pollution) of the generic product.

On the other hand, we can envisage situations where it’s harder to see an overall ‘wellbeing’, or qualitative benefit. Firstly, Zink and Geyer highlight the risk of refill services leading to more refill stations and so more overall consumption of the refillable product. Secondly, they suggest that increased emphasis on recycling could encourage people to buy greater quantities of disposable products, believing they can ‘erase their impact at the recycling bin’.

The growth conundrum

Although we may be able to alleviate some of their concerns about rebound, Zink and Geyer warn of bigger issues linked to the underlying premises of the circular economy. Drawing our attention to those white papers from consultancies and think tanks, focused on how the circular economy can perpetuate economic growth, they highlight a major 2015 study from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The report, Growth Within, says ‘the circular economy would enable Europe to increase resource productivity by up to 3% annually, which would translate to a gross domestic product (GDP) increase of up to 7% by 2030 relative to the current development scenario.’

Zink and Geyer see this as a ‘clear implication is that the circular economy will create growth—growth means the rebound effect and a reduction in expected environmental benefits.’

As Zink and Geyer point out, ‘it turns out that simply closing material loops is not enough to guarantee environmental improvement.’ They suggest the criteria for assessing whether rebound has occurred is to ask whether a given circular economy intervention results in a rise for total production. If it does, they say, that’s rebound.

Can we have further economic growth without increasing our footprint – our impact on resources, nature and climate? That seems to be the billion-dollar question. It’s clear that we must shrink our footprint, urgently. We need to find ways of improving living standards – especially for those on lower incomes – without increasing our global footprint.

This is at the core of those enormous, inter-related, complex – ‘wicked’ – problems facing all of us, as I described in the first part of this article.

The Global Footprint Network makes it clear: every year, since 1970, we’ve been using the resources of more than one planet to fund our lifestyles – we overshoot the earth’s biocapacity. And you won’t be surprised that the problem is caused mainly by those people with higher-incomes – our only solution is to consume less, so we produce less.

The challenge is: how best can the circular economy and regenerative approaches improve living standards, ‘levelling up’ so everyone can access and afford decent housing, good food, and the elements of healthy and enjoyable living that many of us take for granted?

Circular interventions can shrink our global footprint: either by displacing existing products with something that has a smaller footprint, or by reducing the footprints of existing products.

Business can succeed, and make profits, by using different strategies. Designing within the constraints of finite resources, a system where we need to regenerate everything we use, choose safe materials, and waste nothing. What’s important is thinking about how to create value by first shrinking, then closing the loop on your products and materials.

What would an enlightened economist say?

Economist Kenneth Boulding, in his paper from 1966, explained the difference between open (‘cowboy’) systems and closed (‘spaceship Earth’) systems, summarising the problems caused by our delusion that we live in an open system, with resources coming from outside the system, and our waste and pollution being dealt with somewhere else. From a local perspective – a sub-system – that is possible. But of course, at a global scale, it can’t work like that.

It’s becoming clear to more of us that we need different approaches, suitable for a closed system, with limited resources and sinks for our waste. And as Kenneth Boulding said, that means exponential growth cannot continue. We need a different mindset, and a better, circular, AND sustainable system.

Stay in touch so you don’t miss out on our articles, podcasts and other useful stuff we share. Here’s the link to first article in this mini-series, on False Solutions. If you’d like to read more on Greenwash, here’s a an article I wrote earlier this year: Is greenwashing undermining YOUR sustainability work?

Catherine Weetman advises businesses, gives workshops & talks, and writes about the circular economy. Her award-winning Circular Economy Handbook explains the concept and practicalities, in plain English. It includes lots of real examples and tips on getting started.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or stay in touch to get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…