How sustainable is your bike?

8 minute read

We look at the latest in circular economy bicycle design…

We’re probably all confident that travelling by bicycle (even an electric bike) is more sustainable than using a car, and maybe even better than the bus or the train. Bike ‘sharing’ (renting), bike libraries and reuse schemes are popping up – but how well are bikes designed?

At first glance, the bicycle design seems timeless: using straightforward materials and components that most home mechanics can maintain and repair.

Until around a decade ago, that was pretty true. Steel frames were built to last and could be repaired. You could tour the world with your bike, confident in the knowledge that could you buy any parts that wore out. A local repair shop, (or for serious stuff, a welder), could get you back on the road.

Take, make, waste…

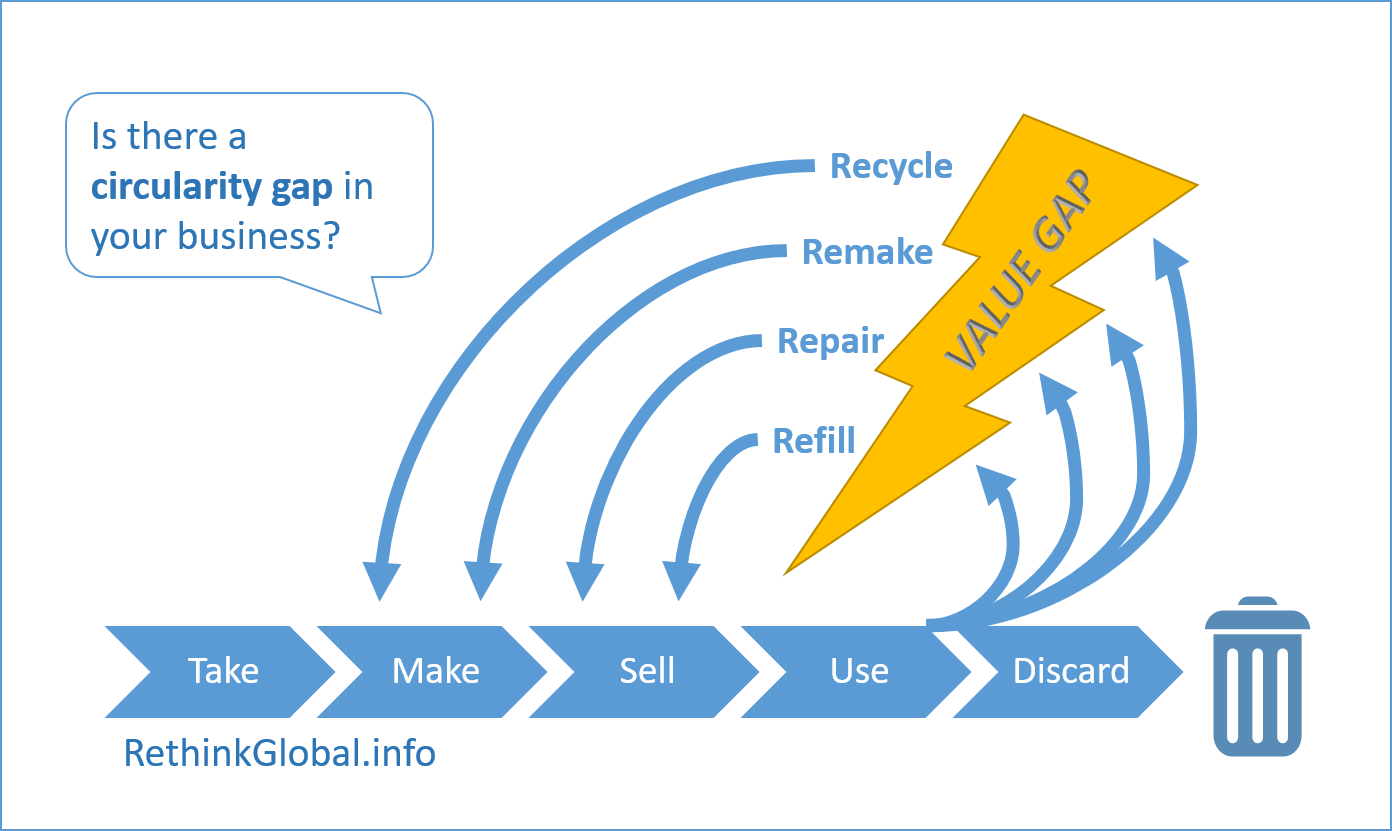

These days, many bicycle brands rely on ‘linear economy’ business models. They want to sell us more stuff, with ever-shorter lifespans. To begin with, they use marketing psychology to encourage us to buy the latest model. That means lightweight frames, different wheel sizes and more gears (even electronic gear-shifting!). What’s more, they design complex components containing multiple materials, often bonded together. We could even accuse them of using planned obsolescence strategies to undermine our ‘right to repair’.

Why do I say this? For example, manufacturers make the component difficult to repair or replace. All too often, repair needs expensive special tools, there are no instructions, and the sale of spare parts is discontinued as soon as legally allowed. Being cynical, it feels like they’re adopting approaches used by the car industry.

Worryingly, frame standards are changing, so replacement of the crankset (the pedals, ‘crank arms’, chainring gears and the ‘bottom bracket’ axle) is impossible because newer ones are completely incompatible. In my mountain-biking days, I used to build my own bikes from scratch and do all my own repairs. Now, I’d be furious about how expensive bikes quickly become irreparable and worthless. What’s more, it’s nearly impossible to do your own maintenance and repairs.

Utility versus Fashion

Sadly, it seems bikes are becoming a fashion statement. Back in 2013, Bike EU reported that ‘China’s new upper class is buying bicycles that cost more than the average citizen makes in three years. While it now is the world’s biggest auto market, the bicycle has become a new status symbol for wealthy and health-conscious executives.’ Another article by Rodriquez Bikes, in Seattle USA, observes that: ‘Bicycle manufacturers need to sell bikes to stay in business. This can lead to some design decisions whose sole purpose is to drive future sales. This is called planned obsolescence.’ In other words, the design will be replaced by something new (and incompatible with the old one). Your bike or components will be obsolete – but don’t worry, the manufacturer will be there to sell you the new model!

So let’s investigate – are sustainable, recycled or renewable materials used? Are components designed to be easily repaired or remade? How durable, repairable and functional are the designs and the materials? Let’s take a closer look.

Frame and tube materials

More recently, ‘performance’ bikes are adopting titanium and carbon fibre frames, handlebars and seat-posts, both for road cycling and mountain biking. These materials are chosen for their high strength-to-weight ratios and resistance to corrosion and fatigue. However, they are very expensive, hard to repair (pretty much impossible for carbon fibre) and have heavy environmental footprints.[i]

Three-times British Cyclocross champion Isla Rowntree asks us to “imagine a time when raw materials are so scarce and costly that it’s no longer viable to make new bicycles.”

A cycling revolution

In 2006, she set out to start a revolution, designing high-quality, durable children’s bikes. Now she wants to create fully sustainable bikes with a closed-loop supply chain.

The Islabikes Imagine project is rethinking how bicycles should be made and supplied. For the frames, stainless steel has been selected for its strength, low weight, fatigue- and corrosion-resistance. The steel is produced in Sheffield (UK), not far from Islabikes HQ. Islabikes says stainless steel already contains 70 per cent recycled content, and around 80 per cent of stainless steel is recycled.

“Light, strong, cheap – pick any two”

Keith Bontrager – bike designer and former President of Trek Bicycles

In a different approach, Swedish brand Vélosophy has used aluminium for its RE:CYCLE project. By collaborating with Nespresso, end of use aluminium coffee capsules are recycled to make the bike frame. In each bike, over 300 used Nespresso capsules account for 30 per cent of the aluminium frame tubes. Vélosophy tell me this is the maximum level under the current regulations.

What’s more, Vélosophy has a social purpose too – its One for One promise supports ‘young schoolgirls in developing countries by donating a bicycle for every Vélosophy sold.’

Although recycling is better than dumping the capsules, clearly reuse (refilling) is a more sustainable option. The business benefits of reuse include retaining more of the original value and using less energy. Want to know more? You can read our blogs on why reuse is the #1 too in the circular economy toolbox, and why the best strategy is NOT recycling.

Alternatively, what about renewable materials? Perhaps surprisingly, wood is popping up again as a material for frames, with ash, bamboo and other timbers. Many of the bike designs are aesthetically beautiful, too – check out this article in Road.cc. You can read more about ‘green’ materials for bike frames in this article on Grist, from 2015.

Brakes and gearing

Traditional rim brakes use a simple mechanism to push a brake ‘block’ onto the wheel rim – simple, and cheap. However, a disadvantage of rim brakes is that they wear out both the ‘block’ (rubber compound) and, eventually, the wheel rim itself.

Recently, brake designs have adapted motorcycle technology, with hydraulically-powered disc brakes. These appeared first on mountain bikes, and are now even found on road-racing bikes.

While these provide outstanding braking performance, especially in muddy and wet conditions, they are more complex and expensive than more traditional ‘rim’ brakes. In addition, they need more complex maintenance.

Before disc brakes became common, cars and motorcycles used drum brakes, built into the wheel hub. These have several good design features, being protected from the weather, have good durability and performance, and the brake pads are easily replaced. Drum brakes are still common on commuter bicycles, and Islabikes is investigating their suitability for the Imagine Project bike.

Wheel hubs can also incorporate internal gears. These are found in many designs of commuter and touring bikes, where low-maintenance and robust design is a priority. In contrast, the ‘high-performance’ bike market (road and off-road) uses derailleur gears. Technology developments over the last decade or so have seen ever-thinner and lighter designs, enabling more gears to fit into the same tight space between the wheel hub and the frame. However, lighter and thinner metal wears out more quickly – and is more expensive to produce. Similarly, the chain is also lighter, thinner and more expensive, and wears out in just a few hundred kilometres.

Circular economy bicycle tyres

Next, what about the tyres? You might assume they’re made from rubber, a natural and renewable material, so they are a sustainable choice. But you’d be wrong. Modern tyres use rubber compounds from both synthetic (from petrochemicals) and natural (from latex) sources. Latex from the rubber tree is one of 27 materials on the latest (2017) EU Critical Materials List. (That means it is classed as important and is at risk of supply shortage or disruption.) Globally, demand is outstripping supply, and the rubber tree growing areas (in the ‘rubber belt’ around the Equator) are under immense pressure from climate change. Unsurprisingly, there are lots of ethical issues related to sustainability and deforestation. Unfortunately, the performance characteristics of natural latex can’t be replicated with synthetic rubber, either.

German tyre manufacturer Continental has been working on this issue for a while. Recently, its R&D teams made a breakthrough by discovering a type of dandelion that has the same latex characteristics. Compared to rubber, it is less sensitive to weather and is undemanding to grow. This means it can be grown near Conti’s factory in Germany, on land not suitable for food crops, saving logistics miles (and cost) too. Continental has developed a range of Taraxagum tyres for different applications, including for trucks and bicycles.

Contact points – saddles, grips and pedals

Unsurprisingly, modern bicycle saddles (seats) are generally made from a hard plastic shell, some padding (plastics) and a plastic or leather cover. A few saddle makers, like Brooks, are still using traditional methods, with just leather and metal. However, leather production has its own sustainability issues – check out this article from PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals).

It’s a similar story for the other contact points – the handlebar grips and the pedals. Plastic or synthetic rubber helps make the bars and pedals both comfortable and safe. Interestingly, Islabikes found a pedal made in Taiwan from waste rice husk, and is investigating a more local alternative, ideally made from agricultural waste.

Principles for a circular economy bicycle design

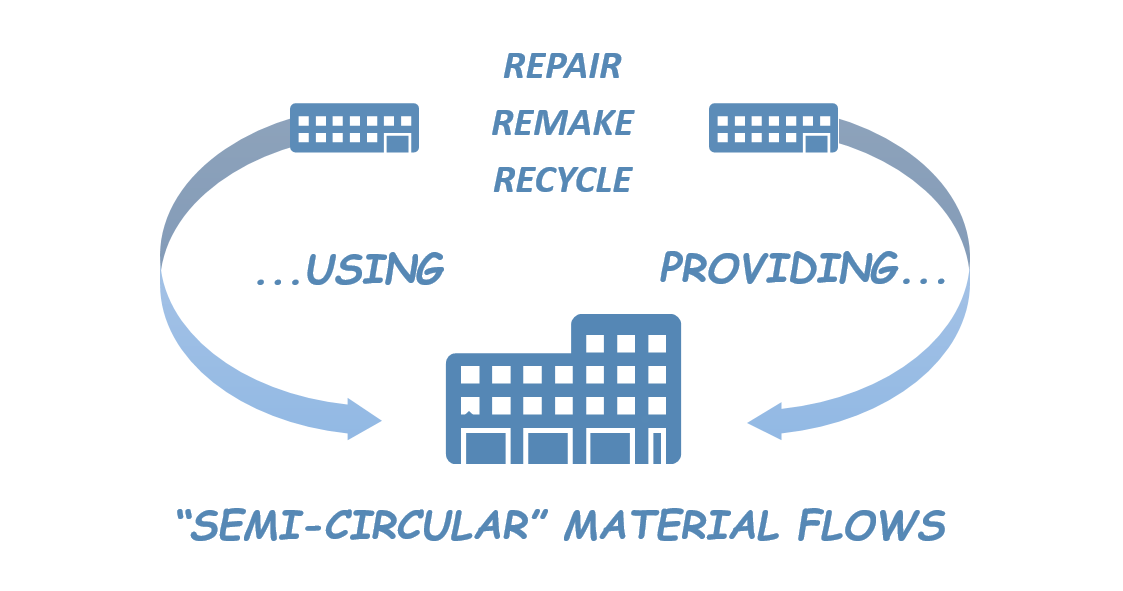

So what does all this add up to? How should bicycle designers be rethinking their approaches, to create a closed-loop system – a circular economy bicycle? The Islabikes Imagine Project is ‘rethinking the way bicycles will be made and supplied in the future’ and has several challenging aims:

- Users will rent their bikes. Once finished with, they return to the factory to be refurbished and rented to another rider.

- Design the bikes so that, at the final end of life, all raw materials can be separated and reused, to create a closed-loop, circular supply chain.

- To source materials and components close to where the bike is made in the UK, to minimise the transport footprint

- Choose materials (including paints) that are easy to separate and reprocess at the end of life, thus maintaining the value of the material.

- Aim for 100 per cent reused materials to remove the need to use finite resources

- The bikes should not need maintaining in the typical rental period, providing a ‘fantastic, hassle-free experience’.

- Each Imagine Project bike should have a 50-year lifespan

A bike for a better world

The bottom line is this: the ‘perfect’ bike should be enjoyable to ride, easy to clean and maintain, and provide good value over its life-cycle.

It’s better for business too, building a strong reputation and engaging customers, suppliers and employees – all of whom what the business to prosper. And of course, not using virgin materials or dumping waste and pollution is better for society and our living planet.

“Utopia is a bicycle that lasts forever”

Isla Rowntree [ii]

If you want to read more about why the most recent designs aren’t necessarily an improvement on the past, have a read of Sheldon Brown’s article here.

[i] https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/knowledge/article/izn20131118-All-Cycling-Frame-Materials-0

[ii] in a video explaining the Imagine Project.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or find out more about Catherine’s award-winning book: A Circular Economy Handbook for Business and Supply Chains.

Why not stay in touch and get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…