Why we can’t recycle our way to a sustainable future

12 minute read.

Should recycling be at the heart of every circular strategy? Waste and recycling has made the headlines recently, with Malaysia sending unrecyclable plastic waste back to Canada and many other countries.

In the UK, a report by consumer group Which found that almost half of supermarket packaging is not easily recyclable. An article in The Guardian highlighted the 11 billion items of packaging waste a year generated by the UK’s ‘lunch on the go’ habit.

We’re becoming more aware of how much we’re wasting, and what damage it is causing, both to living systems and human health. We might conclude that recycling should be our priority for a circular economy strategy.

However, whilst recycling seems much better than landfill, for most products it’s an expensive, energy intensive and ineffective option.

The downsides of recycling

When end-of-life recycling contains mixed materials, the recycled outputs are often only suitable for downcycling into a lower-grade product. Think of clothes, downcycled into wadding for bus seats; and transparent, food-grade plastic down-cycled into park benches. In effect, that means we’re wasting value – of the original materials, together with the energy, water and labour we ‘embedded’ in the product all along the process.

It’s not just packaging going to waste either: in the UK, the average person disposes of 19 garments each year, with seven going straight into the bin. Global discards of electronics and electrical items, were predicted at 49.8 million metric tons in 2018.

Even if packaging is recyclable, it might not be easy to get it into a recycling stream. Consider all the places where you might consume a soft drink: at home, work, out shopping, at sporting and music events etc, plus the range of recycling streams to cater for, and it’s easy to see how complex and expensive recycling can be.

Reputation risk

There are other consequences – difficult to recycle packaging can damage reputations. A report from Surfers Against Sewage made the headlines: highlighting Coca-Cola as the most common source of packaging pollution on UK beaches in a series of 229 beach cleans in April 2019. Volunteers found close to 50,000 pieces of waste, with about 20,000 of these having identifiable brands. Coca-Cola was the leader, followed by Walkers crisps, Cadbury’s, McDonald’s and Nestlé.

Wasting valuable resources

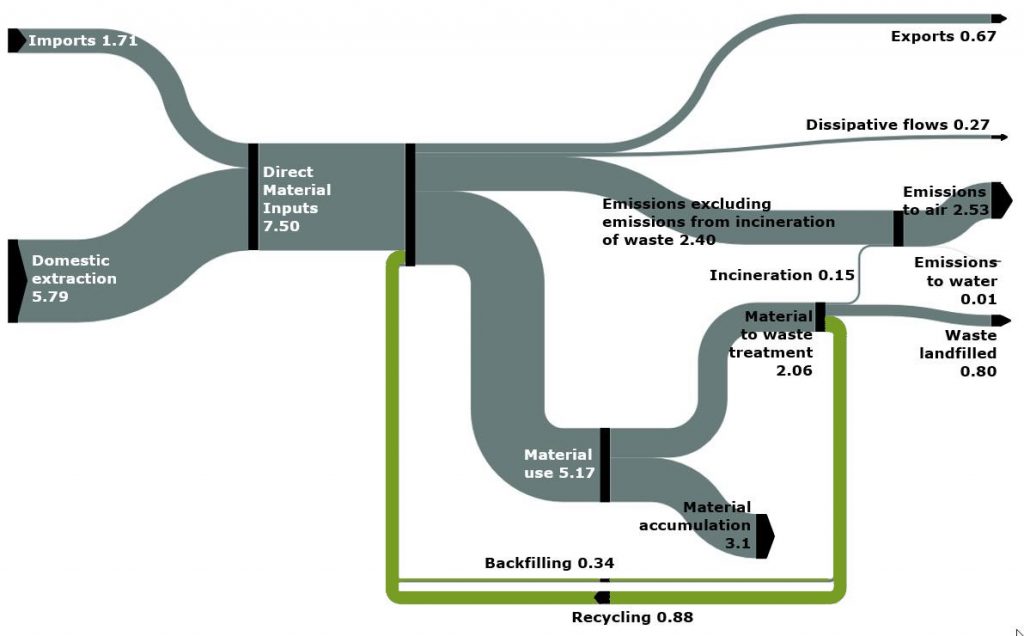

This ‘Sankey’ diagram shows the scale of material flows through the European Union (EU) in 2016. Flowing in from the left are Imports and ‘Domestic extractions’: all the resources we extract, mine, farm, forest, fish for etc within the EU. [An earlier version of the chart, in the Monitoring Framework report [no longer online] highlighted the different materials: metals, non-metallic minerals, biomass and fossil fuels.]

‘Material accumulation’ in the centre describes our ‘stocks’, such as buildings, infrastructure, and products. In other words, if you keep a TV for 5 years, the materials in the TV would show up in the ‘material accumulation’ flow. Later, when you swap the TV for a new one, the materials would show up either in the recycling loop, or as a waste flow. On the right side of the chart, we can see the volume of each type of waste to the air, atmosphere, land and water – dwarfing the flows of exports and recycled materials.

The United Nations predicts that global resource extraction will double by 2050, and Circle Economy’s Circularity Gap report says we recover less than ten per cent of our resources to make them into new products. That pressure on resources is worrying businesses and governments.

Circular economy strategies offer a more effective way of managing our resources, with products and materials staying ‘in the loop’, instead of being wasted. The waste has widespread costs for society: on top of the loss of materials, it causes pollution and damages health for humans and nature. To avoid this, we can find ways to design products and systems that extend the usable lifecycle of products, infrastructure and equipment.

Products with a life of their own

Our first approach should be to design business models and systems to help us get more use (and therefore value), from the product itself. The various circular economy schools of thought, including Cradle to Cradle, The Blue Economy, the Performance Economy and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation have slightly different emphases.

I like to use these four simple principles:

- Use safe, sustainable materials (safe for humans and living systems at every stage).

- Keep products and materials in use for longer, and get more value by sharing and reusing.

- Design out waste and pollution, all waste should either become a new industrial feedstock, or food for nature – compost.

- Regenerate natural systems to secure our future resources.

It’s a mindset shift: using and recirculating instead of owning and consuming, so that products have a ‘life of their own’.

Get loopy!

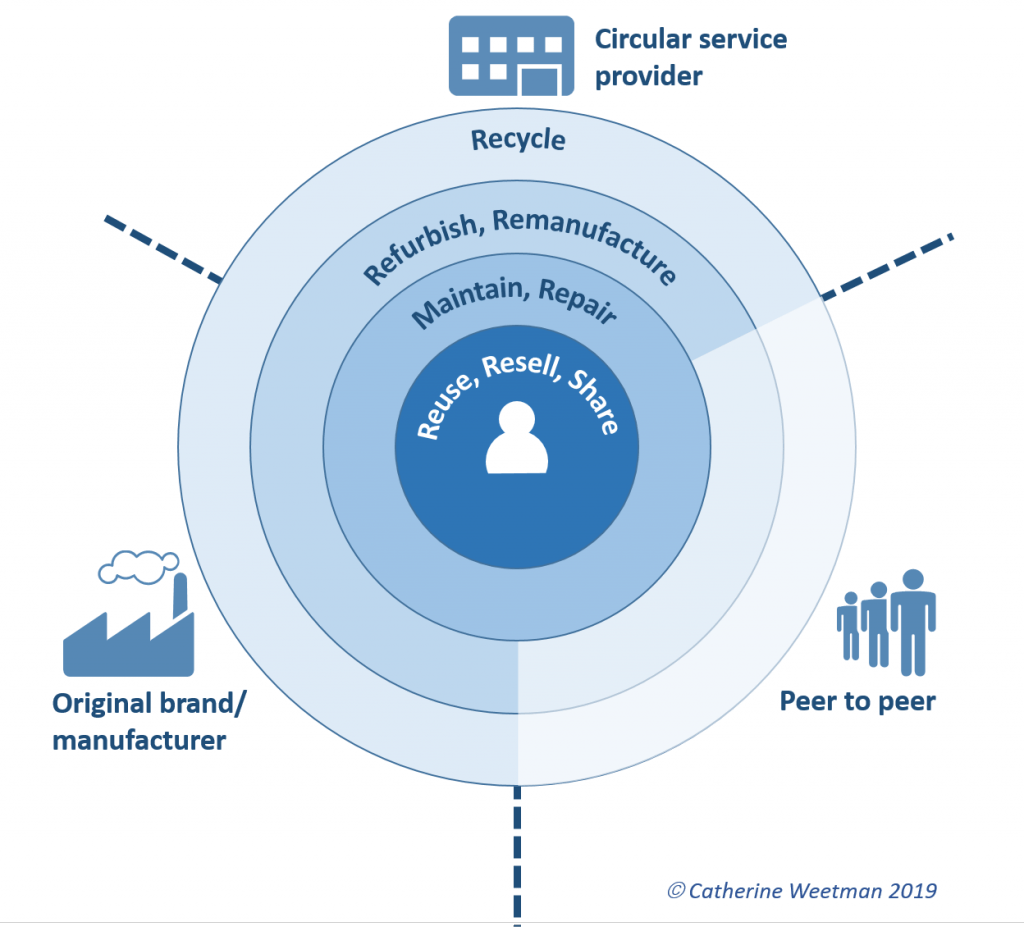

This is my simplified version of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s ‘butterfly diagram’. We’ll explore the four loops in this article, and my diagram shows the three groups who are ‘activating’ circular flows:

- The Brand, or OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer): controlling their own reselling, sharing, maintenance and so on.

- A specialist circular economy provider: reselling, repairing, recycling and even remanufacturing products and equipment made by others.

- The user: who can resell, share and do DIY repairs (with online platforms making this easier).

By aiming for the tightest loops, we can keep products in use with the least effort, re-work, energy and waste. We aim to design products to be durable, repairable, and upgradable, and so they can be easily and effectively dismantled for refurbishment, remaking, and eventually, recycling. That means:

- Using fewer, simpler materials, eliminating glues, laminates and bonding.

- Choosing materials that are easy to recycle, and are abundant and renewable.

- Creating supply chains to ease the recovery of end of use products and materials, supported by business models that encourage access instead of ownership. In this way, responsibility the asset stays with the brand/original manufacturer. A true product stewardship model!

Reuse, resell, share

The inner ‘loop’ should be our preferred circular strategy. Here, success depends on designing durable, robust products and setting up systems for reuse, reselling, and sharing. Reuse and reselling provide a ‘second life’ for the product, with the potential to engage more customers – including those who aspire to the high-quality brand, but can’t justify the cost of a new version.

This inner loop is generally the most efficient and effective option, and retains a much higher percentage of the original product value. For some products, we are already familiar with buying and selling pre-owned and refurbished items (such as cars, houses, jewellery, antiques, etc).

Peer-to-peer reselling is now much easier through eBay, Craigslist, Preloved and other platforms. Specialist websites can provide more assurance of authenticity for high-value products and brands. In fashion, Vestiaire in Europe and Rent the Runway in the US curate clothes for their users, and help ensure the brands are genuine. Specialist sites exist for china and tableware, bicycles, watches, cameras and many more.

Sharing and renting

Forbes tells us that Rent the Runway and clothing rental services “- like Armoire and LeTote – are becoming wildly popular on the heels of education campaigns about the tremendous amount of waste produced by the clothing industry”. The article explains that “our desire to constantly have new things combined with a flourishing $2.4 trillion industry that preys on materialism means that 100 billion items of clothing are now produced annually, 50% of which are disposed of within a year.”

In June, the New York Times reported that The RealReal, the US fashion rental and exchange business, raised over $300m when it floated on Nasdaq. The company, founded in 2011, says it is “the biggest online marketplace for authenticated, consigned luxury goods”. It has carved out “a lucrative niche by employing more than 100 experts, including gemologists and horologists, to authenticate the luxury goods it carries, to reassure buyers worried about counterfeits.”

Also in the US, Urban Outfitters has launched a subscription service, called Nuuly. It will cost $88 a month and allow customers to pick six items — up to a combined value of $800 — to rent, wear, and return, and there is an option to buy favourite items too.

Sharing, or short-term rental services, are becoming more popular, and enable us to get more use out of products or equipment. Familiar examples include car and bike rental services, community tool libraries, even Airbnb. In Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, I described how BMW’s DriveNow car rental service had unforeseen benefits for BMW, engaging potential new buyers of BMW cars.

Packaging with purpose

Making reuse both easy and attractive helps companies to develop new offers. Loop, a ‘global circular shopping platform’ started by recycling specialist Terracycle, aims to transform products and packaging from single use to ‘durable, multi-use, feature-packed designs’. Pilot schemes began in the US and France this spring, and Loop is set to launch in the UK in autumn 2019.

Loop offers food, household personal care products from well-known brands, including Proctor and Gamble, Nestle, PepsiCo and Unilever and more, in upgraded, durable and reusable packaging.

The packs are designed to look attractive in your bathroom and kitchen, and may have other features, for example, containers that keep ice cream cooler for longer.

When the pack is empty, customers place used product containers in the Loop tote, and schedule a free pickup from their home. Loop then cleans and refills the products, and delivers the replenished packs to the customer. Terracyle says the containers recover the environmental cost of production after three to four uses.

What’s in it for the brands? It creates a direct relationship with the consumer, with the potential to build trust and brand loyalty, getting to know more about how they use the product. In contrast, the traditional distribution method puts the brand is under constant price pressure from low-cost supermarkets and Amazon. (Apparently, one of Jeff Bezos’ mottos is “your margin is my opportunity”.)

Repair and maintain

Our next circular ‘loop’ strategy is Repair and Maintain. We think still see these services as ‘normal’ for cars and industrial machinery, but technology has made servicing more complicated, and often it is impossible to access a service manual for ‘DIY’ repairs. In developed economies, clever marketing persuades us to accept shorter product lifetimes and limited, expensive repair options for many products.

But there is a quiet rebellion happening. Repair Cafés are popping up and online ‘wiki’ site iFixit is providing tools, parts and user-friendly instructions to help us repair a wide range of products (almost 150,000 solutions for over 14,000 products in June 2019). There is even a ‘right to repair’ movement, supported by iFixit, which says: “Manufacturers say that repair information is proprietary and [they] work to shut down independent repair shops. Fortunately, not all companies are that way. Support companies that are repair friendly, like Dell and Patagonia. Help us create documentation for companies that aren’t.”

You can read more about Patagonia and Dell in our guide: ‘What is the Circular Economy?’

iFixit users score phones, tablets and other products for ease of repair, with many Apple products achieving very low scores. However, Apple now offers repair with its AppleCare program, reassuring customers that “Apple-certified technicians to repair it with the same precision and care that it was built with. Simply mail in your device or bring it to one of over 500 Apple Store locations and 4500 Apple Authorized Service Providers around the world.”

Government policy can encourage repairs: for example, Sweden is trialling tax incentives for repair of household products. In the European Union, the Ecodesign standards are likely to be expanded to include operational hours, performance and durability of key components, such as with these ecodesign guidelines for vacuum cleaners.

Refurbish and remanufacture

Our next circular strategy is to refurbish and remanufacture the original product or equipment, and this can be ideal for durable products containing some less durable components or materials. These ‘remade’ products can be an attractive option for customers who aspire to the high quality brand, but can’t justify the cost of a new product.

Remanufacturing is not new: Ford has remanufactured car engines since 1930 and Caterpillar and Xerox are well-known for their remanufactured products.

In the United States, the warranty for a remanufactured product has to match that of a new product, and the European Union (EU) is promoting this approach too. The EU identified opportunities for remanufacturing to provide jobs as well as improve resource security by keeping critical materials in the EU, instead of sending our e-waste recycled and made into new products which we often then import again.

There are many resellers of used PCs, and now Dell and Hewlett Packard are recognising the opportunities, selling refurbished products in the UK. In 2019, Fairphone began offering refurbished smartphones across the EU.

Tom Harper of Unusual Rigging Limited talks about the benefits of refurbishing and remaking stage rigging equipment in Episode 3 of the Circular Economy Podcast.

In addition, there are start-up opportunities for specialist remanufacturing companies. Rype Office, a UK start-up, has grown successfully by creating a full-service offer for remanufactured, high-quality office furniture, including a design service [disclosure: I am a minor investor]. Sierra Industries, in America, remanufactures jet airplanes made by reputable companies such as Cessna.

Ecodesign expert Katie Beverley tells us about her favourite remanufacturing examples in Episode 5 of the Circular Economy Podcast

If all else fails - recycle

Our circular strategy of last-resort should be recycling.

Designing for circulation at the outset helps companies make a success of circulating products, components and materials. But, all too often, the difficulty of accessing and identifying materials can make it cost prohibitive – alloys, laminates and bonded or glued materials can be impossible to separate. For example, a report by Green Alliance tells us that a reused iPhone retains almost half its original value, but recycling recovers less than ¼ of one percent of the value of a new phone. In other words, reusing the iPhone recovers 200 times more value, as well as increasing Apple’s customer base – and those new customers are likely to buy music and other subscription services from Apple.

Products are increasingly complex too. The average smartphone contains 62 different elements (ie materials). Even Fairphone 2, designed to be repairable, modular and sustainable, contains 46 different elements. However, Fairphone’s modular design makes it easier and more productive to separate valuable elements like magnesium, tungsten and tantalum.

Some entrepreneurs are creating business opportunities from difficult to recycle materials: upcycling a problem waste into a high-quality product. RubyMoon was probably the first company in the UK to upcycle ocean plastics, turning them into highly durable swimwear and active-wear. For more on this, listen to Jo Godden of RubyMoon in Episode 4 of the Circular Economy Podcast.

Circular strategies – from consuming to using

We are starting to see major players shifting to a service model, where the focus is on using, not consuming. Even brands that have relied on attracting sales through new, enticing designs and planned obsolescence strategies are rethinking.

Apple’s sales of iPhones have slowed, and it’s now developing software and entertainment services to provide a more engaging offer (and more consistent revenue streams). Apple has committed to a circular economy model (albeit without target dates), declaring “we want to one day manufacture products without mining any new materials from the earth.” Apple acknowledges “it’s a big challenge. But we know we can make the best products in the world while leaving the planet better than we found it.”

PepsiCo is already signalling a shift to a lower footprint model with its $3.2 billion acquisition of SodaStream in 2018. If you are in the UK (and old enough!) this may remind you of the ‘milkman’, delivering milk in glass bottles etc to homes, schools, businesses and more, collecting the empties the next day?

Rewards!

As well as the benefits for people and planet, there are fantastic opportunities for business. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Circular Economy 100 includes many well-known international companies. Whilst we might wonder about the extent of change, some of those companies are already publicising the benefits for their bottom line.

Schneider, winner of the Circulars 2019 Multinational award, says “The circular economy is part of everything we do at Schneider: it lowers total cost of ownership for our customers; it preserves precious natural resources for the future; and it creates new revenue and jobs for our own company. It’s a win-win-win for the triple bottom line.”

Schneider’s approach includes:

- Eco-design of products with minimum use of virgin raw materials;

- Circular Value Propositions (connected objects, services, leasing, repair, take-back etc.);

- A circular supply chain including reverse logistics, repair and reconditioning centres

- Four “circular economy” indicators in the quarterly Schneider Sustainability Impact metrics, linked to management reward schemes.

The award summary includes impressive benefits, with 12 per cent circular revenues and plans to avoid 100,000 tonnes of primary resource consumption from 2018-2020.

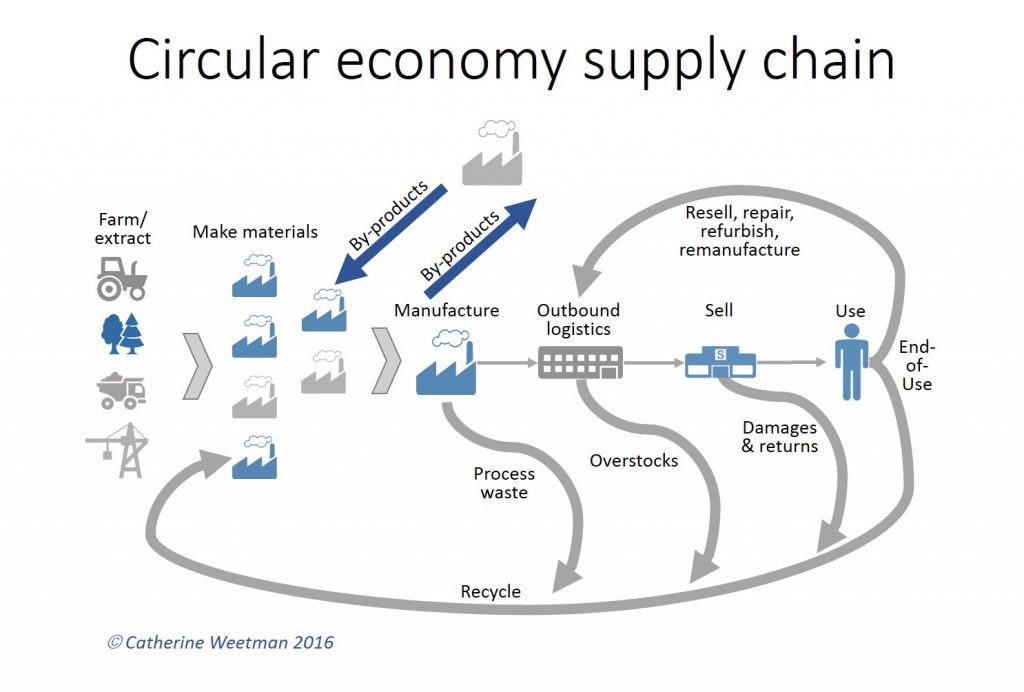

Circulating value: from leaky to loopy

The circular economy sparks a different way of thinking: seeing business models and supply chains as part of complex, interconnected systems, all dependent on earth and nature.

Envisaging the system helps us to identify where waste is leaking out. We can ask critical questions – where, what and how – to understand they ways we are losing the materials, energy, water and even labour we invested in the product. How can we find ways to retain that value in our system, and circulate it, sharing it with our customers, suppliers, employees and partners?

The tightest loops retain most value, but need radical redesign of both business model and supply chain: regenerating, circulating and capturing value instead of take, make and waste.

We can’t do business on a dead planet. Instead, we need to rethink waste and circulate value.

If you want to learn more about the circular economy, read our guide “What is the Circular Economy?” or listen to Catherine’s interviews with businesses and those people making the circular economy happen, on the Circular Economy Podcast.